The After Series: How Loved Ones Live On in a Digital Age

We spend so much of our waking lives avoiding death—in more ways than one. When it comes to talking about the inevitable, it isn’t always easy. So the Orange Dot is aiming to shine a light on these stories, in hopes that it may help others. The After Series features essays from people around the world who’ve experienced loss and want to share what comes after.

The technician at the AV Transfer House in Hollywood tested the video I handed him. I watched from the other side of the counter. It had taken me years to bring in the VHS of my dad’s news segment about elderly men on hospice facing their mortality. My dad wasn’t the newscaster; he was one of the patients.

My mother and I had left my father when I was three years old, escaping his alcoholism by moving in with my grandmother. I saw him often as a child, and less so as I got older. His broken promises over the years had stacked higher and higher until I could no longer see above the fray. At 21, in an attempt to keep our connection without seeing him face-to-face, I began writing him letters. Our correspondence continued for three years until, one day, my mom called to tell me Dad had terminal lung cancer. I flew home to say goodbye and ended up taking care of him in his final days. It was nice to have those last in-person moments with my dad, but I didn’t cry the way I felt I was supposed to. Instead, I felt like an enormous weight of disappointment would soon be lifted from my shoulders. The weight did lift, and in its place I tried to fill the void he had left behind. I listened to countless stories about him from my mother and from a cousin I barely knew. I read the newspaper clippings about his activism and stared at the small stack of photos of us together more times than I can remember. But when my cousin sent me the VHS two years ago, I couldn’t bring myself to watch it.

I hadn’t prepared myself to watch my dying father for the first time on a large screen in a corner store. At the same time, I knew he’d smile with appreciation at being broadcasted in Hollywood—even if it was only to be transferred to DVD. A fuzzy image of the newscaster announced the segment. Seconds later, my father appeared, an oxygen tube protruding from his nostrils. My eyes welled up, and I felt awash with relief at my reaction. “That’s my dad,” I told the tech. I felt nothing when my dad was dying. Or rather, I felt a sense of resolution and the accompanying guilt that often comes with such a response.

I told anyone who would listen that I’d order the transfer just as soon as I had the $15 to do so. It’s true that I had been extremely tight on money for the past two years, but not so tight that I couldn’t afford to splurge on this important artifact. It wasn’t until recently that I finally realized what had been holding me back: both the fear of feeling nothing and the fear of feeling too much. Besides that, it also dawned on me that once I’d watched the footage, my dad would never say anything new to me again. I had been hoarding his final goodbye. When I returned home with the DVD a couple days later, those close to me urged me to rip off the Band-Aid. Friends would tell me, “It’s taking up unnecessary space in your psyche. You think you’re putting it off until you’re ready, but you’re really making it bigger.” In the end, the news segment was incredibly short, and my dad was one of three men who were interviewed. I got teary as he looked directly at the camera and spoke about the daughter he loved so much. But the best part of the video is the hiccup in the middle of the interview: the screen cuts to blue and then comes back in with waves of static before finally catching up with my dad’s conversation. I will never know what he said in those brief seconds. I’m comforted by the reality that he will always have more words out there in the universe that I haven’t yet heard. When I close my eyes, I can see him on that big screen, just as clearly as the hand-written letters I’ve kept all these years.

. . .

Submissions for The After Series are now closed. We continue to explore and discuss mental health (and everything else that occurs around life and death) on The Orange Dot.

Be kind to your mind

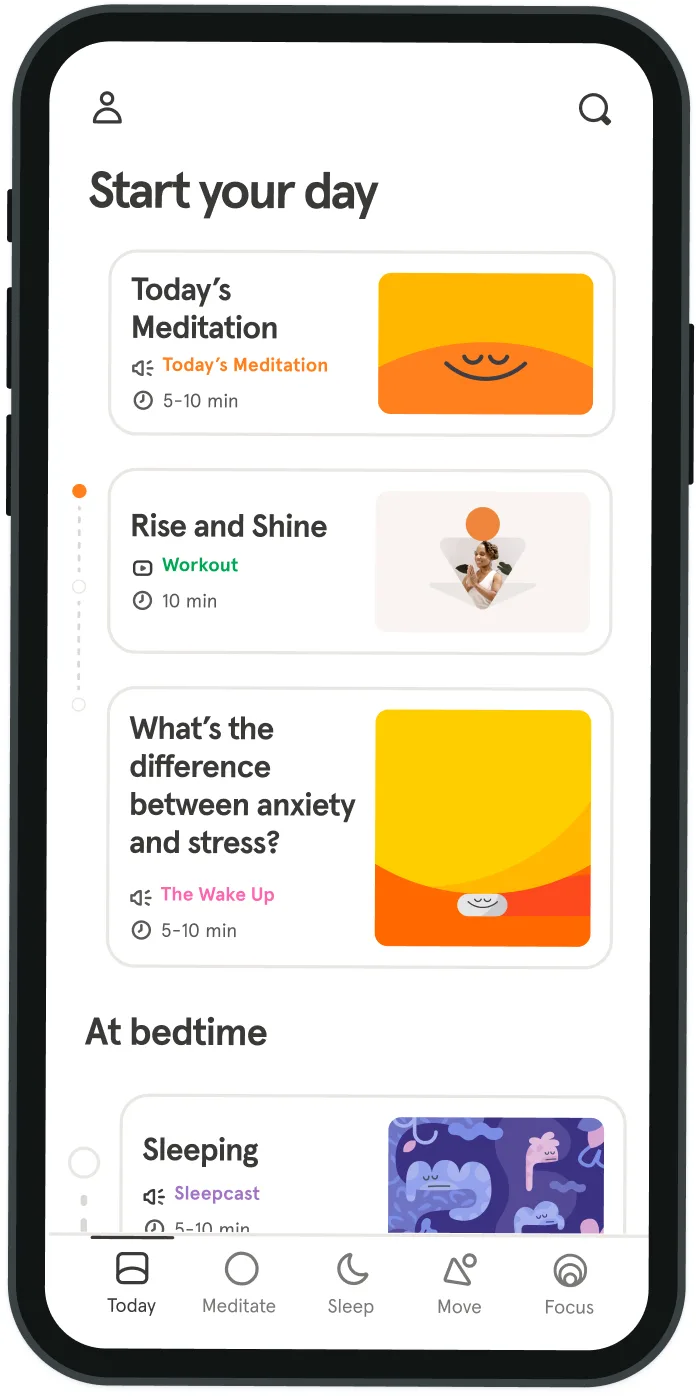

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

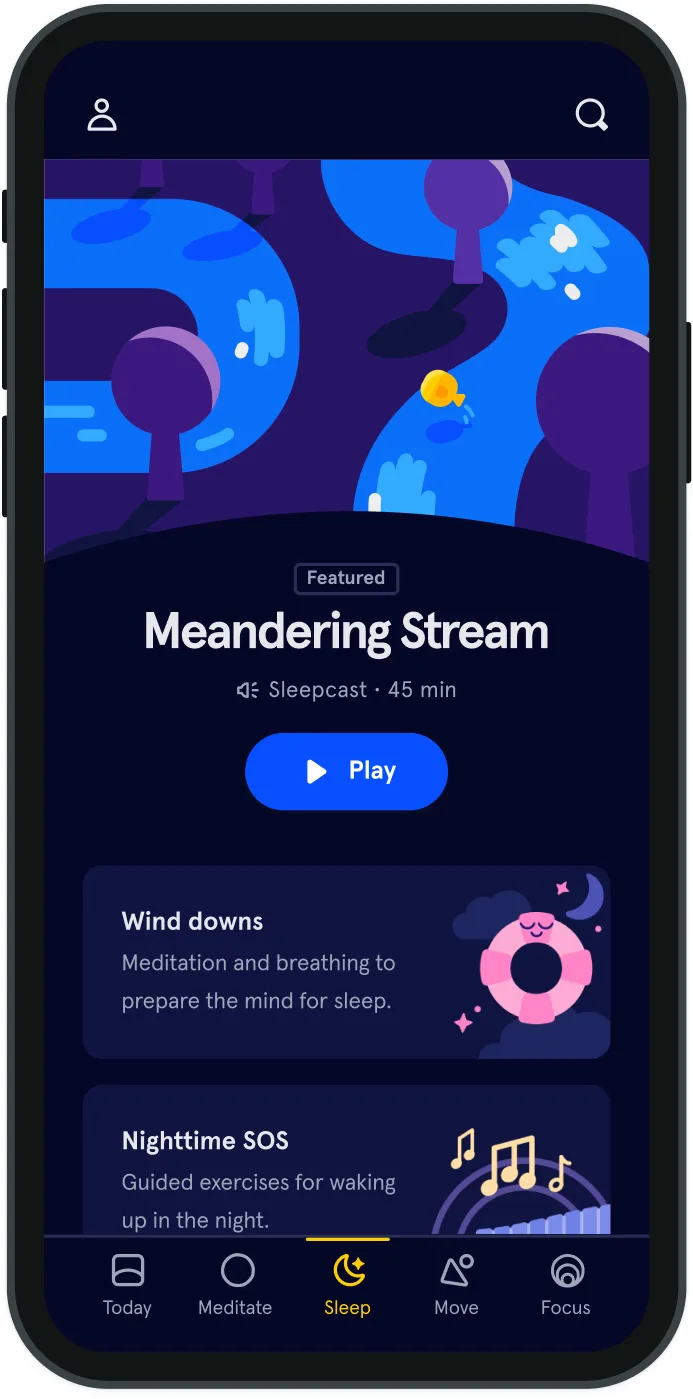

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice