The science of giving yourself a pep talk

When times get tough, some of us rely on our inner voice by default for direction:

"You got this, Jennifer!" "I need to get out of my head. I'll go out for a walk." "Dinnie doesn't sweat the small stuff. She likes to move on—just like she is going to do now." Techniques such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) also use methods that involve self-dialogue, and recent research shows that self-talk may also help us navigate rough patches. A new study suggests that people can conquer stress if they address themselves in third person: "Ali has never aced this exam, and that's why his hands are shivering. But all Ali needs to do is face his fears and take the test."

Quick and easy

Jason Moser, associate professor of psychology at Michigan State University and a co-author of this study, noticed people using third person self-talk during daily conversation. "We wondered: are people doing it by accident? Or is it just a weird quirk of people who are troubled? Is it actually something useful?" says Moser. Moser, who also works as a therapist, has clients who are less inclined to practice traditional therapies such as CBT and was curious to explore alternatives. The study consisted of two experiments. During the first, researchers showed college students violent images and asked the participants to reflect silently using either first person (I think this is really grossing me out!) or third person (Sanjay is getting grossed out by this image!) self-talk. With the help of electroencephalography (EEG), researchers were able to also track brain activity in the regions that govern emotions. By observing the pattern of this activity, they were able to determine whether or not third person self-talk was helpful in keeping emotions in check. During the second experiment, subjects were asked to reflect on painful past experiences using first person or third person self-talk, while their brains were scanned using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which tracks brain activity in areas that relate to emotional regulation.

Moser says that both experiments produced the same finding: "When people use third person self-talk, emotion-related brain activity was significantly reduced, suggesting they were regulating their emotion." There was another startling revelation. Third person self-talk was neither taxing nor required much brain power—at least not more than a standard pep talk. "Nowhere in either study did we see brain activation related to effort for attention or thinking or planning," says Moser. Is there some kind of magic in self-talk? What makes it more useful than r first person self-talk? The problem with first person cheering is the use of words such as 'I' and 'me.' "Those words are completely tied to your 'self', whereas your name creates a little bit of psychological distance because it refers to lots of people," says Moser. "There are Jasons in TV and movies. That little bit of psychological distance from myself to make it look as though I'm thinking about somebody else." That's why third person reflections can quickly provide perspective, and also encourage solutions. Moser also clarifies that self-talk isn't merely a pep talk designed to make us feel good. Instead, we can note the situation and experience it from beginning to end.

Do it right

Although the research on this subject is relatively new, experts not associated with the study have found the results promising. "I can help people examine what troubles them more dispassionately than they could do on their own," says Andrea Brandt, Ph.D., a marriage and family therapist in Santa Monica, Calif. "You need space between yourself and your emotions. It makes sense then that third person self-talk could help people regulate stress." Though the study didn't specifically look at first person self-talk, experts suggest it's not useless. If trying to lift your spirits using 'I' and 'me', here are a few tips to keep in mind: 1. Try to sound natural and realistic. "You want self-talk to sound like it's coming from a loving parent or close friend," says Brandt. "If your best friend felt stressed about work, what would you say to him or her? Now, try saying that to yourself." And remember to be kind to yourself. 2. Create space between your thoughts and your reactions. Stephanie Kriesberg, Psy. D, a licensed psychologist in Concord, Massachusetts, suggests "externalizing" your fear. "You think of your worry, fear, anger—whatever the problem may be—as something outside of yourself." Let's say you're a father who is having a difficult time putting your son to bed. You are frustrated and feel like yelling. "So when you feel you are starting to lose your cool, you can say to [yourself]: 'This is my frustration talking. It loves to get me yelling, but I don’t need to listen to it. I’ll take a walk around the house and calm down.'" 3. Breathe deeply. Take deep breaths before you begin self-talk. It will help calm your nerves. This piece was produced in partnership with Nike Training Club. To get started on your fitness journey, download the NTC app here.

Be kind to your mind

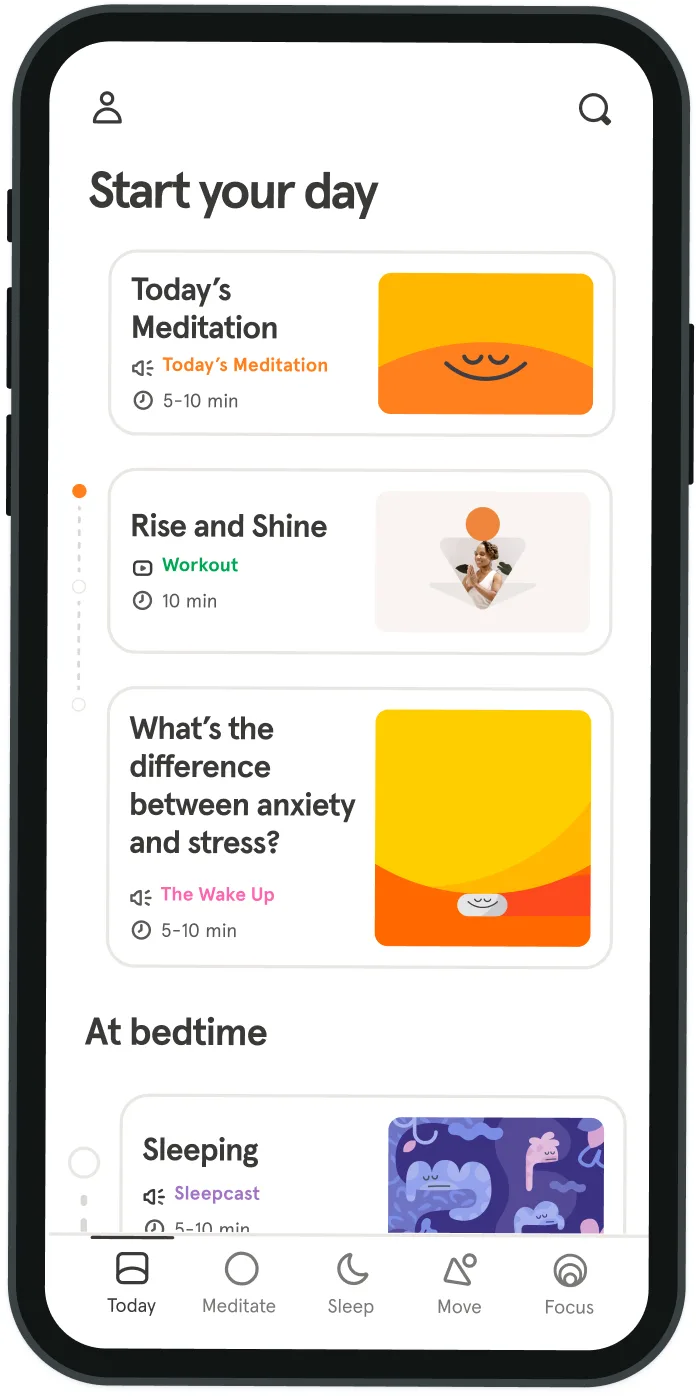

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice