The After Series: From Grief to Gratitude

We spend so much of our waking lives avoiding death—in more ways than one. When it comes to talking about the inevitable, it isn’t always easy. So the Orange Dot is aiming to shine a light on these stories, in hopes that it may help others. The After Series features essays from people around the world who’ve experienced loss and want to share what comes after.

Alison Schofield was stifled from grieving right from the start. The 30-something Toronto resident first heard about her partner's death while she was riding in a huge truck down a highway at rush hour. Alison and her partner Paul, a paraplegic, had been living on different continents when her best friend called to report that he had succumbed to a sudden massive infection.

Schofield’s inability to find a confidante made her bereavement especially lonely. She missed Paul's advice and begged for him to appear in her dreams. Once she attended a support group, but couldn’t relate to the middle-aged participants who were discussing life insurance and children. Easthope worries about young grievers who have to muzzle their feelings. Pent-up hurt can fizzle into chronic sadness or irritation. It can even morph into physical symptoms like diarrhea and skin rashes, says Easthope. Luckily, Schofield discovered The Dinner Party before her health became compromised. The U.S.-based group caters to bereaved people in their 20s and 30s, says its co-founder, the Los Angeles-based Lennon Flowers. Potluck gatherings are thrown in the homes of facilitators, and partygoers are invited to share their healing journeys in a welcoming environment where it’s OK to be authentic. “People are hungry for the opportunity to tell their stories,” says Flowers. Since there were no dinner parties in Canada, Schofield established the first one in Toronto in 2015. Schofield, like all other hosts, received training from The Dinner Party founders. Hosts are taught to leave some tasks undone while guests are arriving, encouraging them to set the table or hand out drinks, says Flowers. This makes them comfortable before plunging into the deep end of their sorrows. Hosts then propose a toast for the participants, encouraging each to relate how they’re doing. The food is supplied by the party-goers, often based on recipes from their lost loved ones. Conversations are unscripted. “There are no incorrect topics,” says Flowers.

“I had the most horrifying feeling I’ve ever experienced,” Alison says. She was only 26 years old and had never bid goodbye to anyone significant. But she knew that she couldn’t give voice to her sorrow in this steaming hot vehicle packed with colleagues. It was her organization’s major yearly fundraiser and she felt that "there was no option of going home—and even if I went home it wouldn’t change anything." Schofield continued to struggle while mourning. “It was the first time the concept of never really entered my life—never hear his voice again, never kiss him again, never feel him,” she says. The distance that had crept into her friendships only compounded her distress. When she tried to talk about her pain, her buddies’ bodies went rigid. “They didn’t know if they had to comfort me,” she says. Toronto grief counselor Tom Easthope is not surprised by the reaction of Schofield’s friends. We live in a death-phobic society, he says. “People just want to change the subject when someone has bad news,” says Easthope. And it’s even harder for people who haven’t lost anyone to comfort bereaved friends.

Easthope recognizes the healing potential for The Dinner Party. Sharing an informal meal helps to break down barriers and greases communication, he says. The get-togethers also allow young mourners to express their feelings without alienating their friends. The camaraderie is a tonic for loneliness. “You get a boost because you’re understood and not judged,” he says. Grievers take comfort from hearing the journeys of their peers. “When people see others going through a similar process, they realize that they’re normal and not going crazy,” says Easthope. The dinner parties were certainly comforting for Schofield. Her living room, a quiet and comfortable space, was conducive to conversation. So were the wine and the food. “At dinner, you can joke and be more casual than at a bereavement group,” she says. Schofield relished connecting to other bereaved youngsters at her stage of life—she could bring up Tinder without having to explain what that was. The dinner also provided a haven where she could be herself. Instead of maintaining a happy façade, she could tell her guests that she cried herself to sleep every night or that she talked to her late lover. Schofield also made some lifelong friends from the group. “It’s healing just knowing that you’re not alone,” she says. Today, Schofield is thriving. Hosting The Dinner Party has given her a newfound sense of purpose. “When I’ve talked about The Dinner Party at work or in class it gives people the courage to tell their own stories,” she says. Breaking down the taboos around grief is satisfying for her. And though she still has bad days, she’s come to terms with her life. “I feel lucky that I was loved so much,” she says.

Be kind to your mind

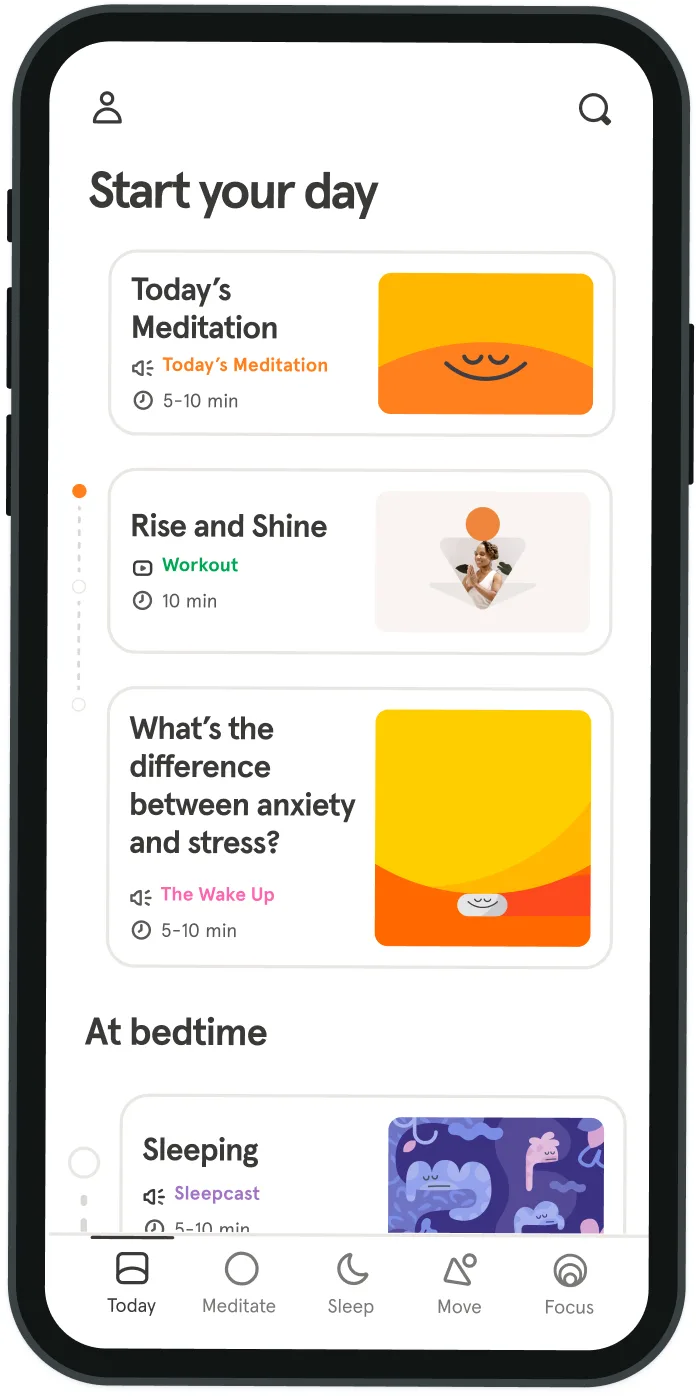

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

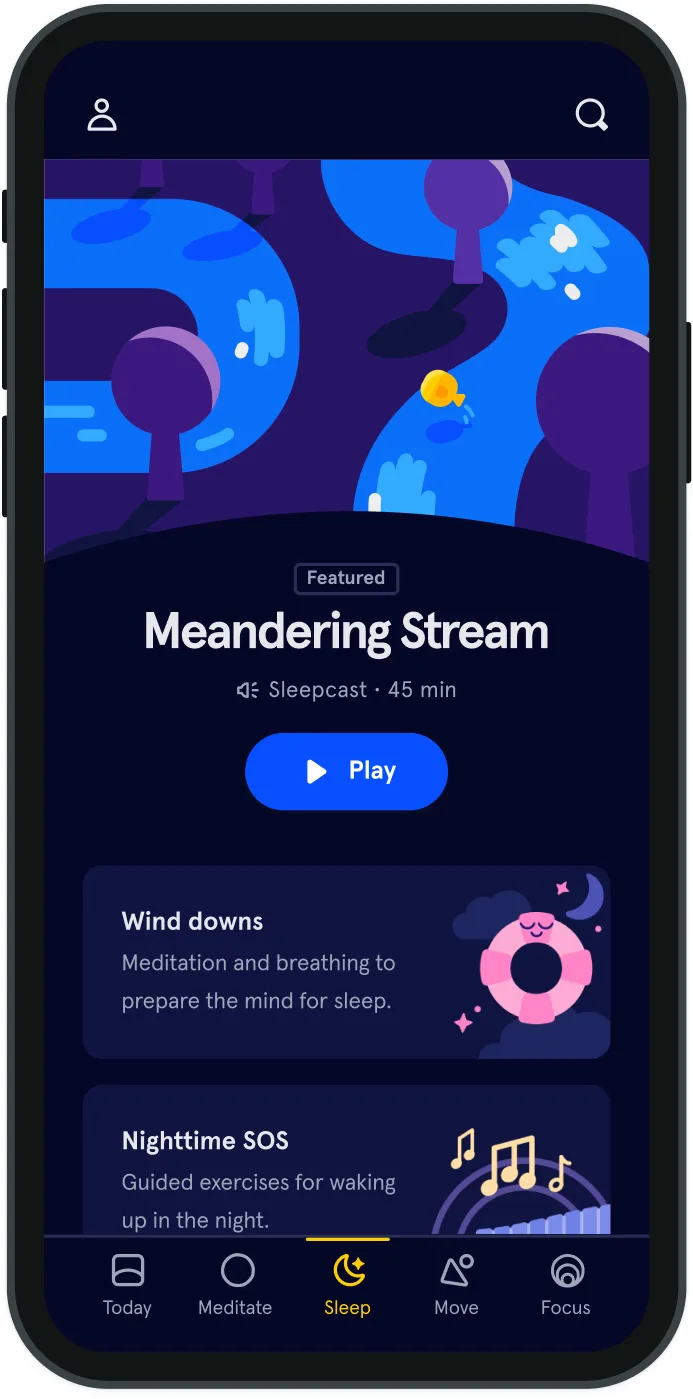

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice