Power to the playlist: are you listening to music that can change your life?

Before heading to the starting line for the ten-kilometer race, Ethiopian long distance runner Haile Gebrselassie approached the DJ with a request. The DJ assented. The race began, Scatman John's “Scatman” seeped out of the speakers and wafted over the track, and Gebrselassie set a new world record. He completed the race in under 26 minutes and 22 seconds.

Afterward, he revealed that without the song, the new world record wouldn’t be his. The song’s beat allowed him to run at a faster clip. “I did many records with the Scatman song,” he later told The Guardian. “Fantastic.” As a boy, I dreamed of being a professional soccer player. I spent countless hours jumping rope, working on my footwork, and kicking a ball against my parents’ garage door. But I had more passion than talent. I wasn’t tall enough, I wasn’t big enough, I wasn’t skilled enough. And, perhaps most of all, in a sport that prizes sprinting speed so highly, I was slow. By the age of 15, I had reluctantly realized these realities. But learning of Haile’s feat with the Scatman song, my mind meandered back to my youthful dream. Maybe fusing music with training could have improved my odds of playing alongside Cristiano Ronaldo. Maybe I could be playing in front of adoring crowds instead of typing this sentence. Maybe. Former Italian professional basketball player Matteo Brunamonti, 33, who played for Virtus Pallacanestro Bologna, a top team in Italy, also experienced the impact of music. “Right before the game, when the players are warming up, the music played in the arena isn’t just entertainment for the crowd,” Brunamonti explained. “Players would ask for certain songs before the game, one of the top players even created a list for the DJ to play during the warmup—it would pump you up and make you more confident.”

In fact, researchers have gathered a great deal of knowledge about how music impacts athletic performance. And it’s far from a placebo effect; athletes can run faster, lift heavier, and improve endurance levels all because of music. Costas Karageorghis, a sports psychologist at London's Brunel University and author of “Applying Music in Exercise and Sport”, has even compared music to a performance enhancing drug. Karageorghis’s fascination with music began as a child in the 1970s in a poor neighborhood of South London. He lived with his extended family in an apartment above a second-hand record store. Early in the morning, the shop played music and a “thundering baseline” would jolt Karageorghis out of bed. He’d wipe the sleep from his eyes, look out the window, and watch as people’s facial expressions and walks would transform as they would come within earshot of the music. “It would put a lilt in their stride,” Karageorghis said. He’s devoted his career to understand how and why. According to Karageorghis, music can serve as a stimulant that helps athletes attain an optimal mindset before competition. Songs with strong emotional associations that conjure images of heroic feats or underdog victories—think Vangelis' “Chariots of Fire,” Chumbawamba's “Tubthumping,” or Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger”—work best. But Karageorghis stressed that there aren’t any “perfect tracks.” People have different reactions to songs based on sociocultural backgrounds and musical tastes, along with the type and intensity of activity being done. Although athletes aren’t allowed to wear headphones or listen to music during most professional events, many use music during training. Music distracts the mind and reduces the perception of how hard we think we’re working. This makes relatively difficult workouts feel easier and imbues athletes with greater staying power. As Karageorghis explains it, the body’s musculature and vital organs communicate with the brain through the Afferent Nervous System. Music can block some of the messages that travel back and forth, preventing the brain from receiving all the information about how hard the muscles are working. “If we think about it as analogous to internet bandwidth in that it’s limited in how much information it can transport at any given point, it appears that music uses up some of that bandwidth and it blocks fatigue related symptoms from entering focal awareness,” Karageorghis said. Runners can enhance workouts by using a song’s beat as a metronome and syncing their stride. This can make it much easier to maintain a steady pace and can reduce energy loss by unnecessary movements. (As an aside, many runners actually do train with metronomes for this very reason.) But there’s a caveat. There’s a rock hard ceiling. Music between 120 and 140 beats per minutes is the sweet spot, anything above that won’t make you any faster. Music, moreover, is only effective at low to moderate intensity levels. Beyond 75 percent of aerobic capacity, the messages that the muscles and organs put out overwhelm the Afferent Nervous System, Karageorghis said. This deadens music’s effect on lowering perceived exertion. But the right song can still be effective in enhancing mood during the exercise, helping endurance. And don’t ditch the songs after competitions and workouts, either. Music can send heart rates tumbling, slash blood pressure levels, and reduce cortisol and negative emotions. This helps athletes recuperate and achieve resting state faster. Karageorghis has done research into, and designed track playlists especially for, post-activity recuperation. The playlist music starts off at 140 beats per minute—more than two beats per second—and over twenty minutes gradually falls to 60 beats per minute (BPM). “It provides a warm mattress of sound that leaves them feeling refreshed and revitalized,” Karageorghis said. Music can be a powerful tool that should be used wisely. Listening with earphones—today’s norm—can cause short-term hearing loss, and long-term hearing damage, like tinnitus. Karageorghis cautions not to use headphones for more than an hour a day, and to keep the volume low enough to easily maintain a conversation with a person close by. Karageorghis has worked with many elite athletes over the years, including world champion Welsh hurdler Dai Greene. For Greene, Karageorghis worked with music producer DJ Redlight in 2012 to make a song specially tailored for Greene’s training called “Talk to the Drum." Other athletes have discovered music’s potency independently. Nicole Sifuentes, 31, a Canadian middle distance runner and Olympian, said that she inadvertently saw how certain songs could impact her running times during training. “I’m not getting faster,” she said. “But it helps me maintain the pace I want to be at when I’m getting tired.” All this leads me to think that the right music might have improved my strength and endurance levels. But it may not have transformed my sprinting. With or without music, maybe I wasn’t bound for professional sports. For a good workout, check out Costas’ sample workout playlist: Pre-event mental preparation Survivor "Eye Of The Tiger" (109 BPM) Snap! "The Power " (109 BPM) Warm-up Justin Timberlake "Can't Stop The Feeling" (113 BPM) Michael Jackson "The Way You Make Me Feel" (114 BPM) Running John Cafferty "Hearts On Fire" (136 BPM) Bruce Springsteen "Born To Run" (148 BPM) Weight training Clean Bandit "Stronger" (125 BPM) Tiësto "Work Hard Play Hard" (128 BPM) Warm-down Fat Larry's Band "Zoom" (105 BPM) Bill Withers "Lovely Day" (98 BPM) Recuperation/revitalization Stevie Wonder "Ribbon In The Sky" (69 BPM) Joe Cocker "You Are So Beautiful" (62 BPM) [Editor’s Note: A__n__d i__f y__o__u_’r__e i__n t__h__e m__o__o__d f__o__r s__o__m__e__t__h__i__n__g a l__i__t__t__l__e m__o__r__e m__e__d__i__t__a__t__i__v__e,_ c__h__e__c__k o__u__t H__e__a__d__s__p__a__c__e_’_s o__w__n m__e__d__i__t__a__t__i__o__n p__l__a__y__l__i__s__t.]

In fact, researchers have gathered a great deal of knowledge about how music impacts athletic performance. And it’s far from a placebo effect; athletes can run faster, lift heavier, and improve endurance levels all because of music. Costas Karageorghis, a sports psychologist at London's Brunel University and author of “Applying Music in Exercise and Sport”, has even compared music to a performance enhancing drug. Karageorghis’s fascination with music began as a child in the 1970s in a poor neighborhood of South London. He lived with his extended family in an apartment above a second-hand record store. Early in the morning, the shop played music and a “thundering baseline” would jolt Karageorghis out of bed. He’d wipe the sleep from his eyes, look out the window, and watch as people’s facial expressions and walks would transform as they would come within earshot of the music. “It would put a lilt in their stride,” Karageorghis said. He’s devoted his career to understand how and why. According to Karageorghis, music can serve as a stimulant that helps athletes attain an optimal mindset before competition. Songs with strong emotional associations that conjure images of heroic feats or underdog victories—think Vangelis' “Chariots of Fire,” Chumbawamba's “Tubthumping,” or Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger”—work best.

But Karageorghis stressed that there aren’t “perfect tracks." People have different reactions to songs based on sociocultural backgrounds and musical tastes, along with the type and intensity of activity being done. Although athletes aren’t allowed to wear headphones or listen to music during most professional events, many use music during training. Music distracts the mind and reduces the perception of how hard we think we’re working. This makes relatively difficult workouts feel easier and imbues athletes with greater staying power. As Karageorghis explains it, the body’s musculature and vital organs communicate with the brain through the Afferent Nervous System. Music can block some of the messages that travel back and forth, preventing the brain from receiving all the information about how hard the muscles are working. “If we think about it as analogous to internet bandwidth in that it’s limited in how much information it can transport at any given point, it appears that music uses up some of that bandwidth and it blocks fatigue related symptoms from entering focal awareness,” Karageorghis said. Runners can enhance workouts by using a song’s beat as a metronome and syncing their stride. This can make it much easier to maintain a steady pace and can reduce energy loss by unnecessary movements. (As an aside, many runners actually do train with metronomes for this very reason.) But there’s a caveat. There’s a rock hard ceiling. Music between 120 and 140 beats per minutes is the sweet spot, anything above that won’t make you any faster. Music, moreover, is only effective at low to moderate intensity levels. Beyond 75 percent of aerobic capacity, the messages that the muscles and organs put out overwhelm the Afferent Nervous System, Karageorghis said. This deadens music’s effect on lowering perceived exertion. But the right song can still be effective in enhancing mood during the exercise, helping endurance. And don’t ditch the songs after competitions and workouts, either. Music can send heart rates tumbling, slash blood pressure levels, and reduce cortisol and negative emotions. This helps athletes recuperate and achieve resting state faster. Karageorghis has done research into, and designed track playlists especially for, post-activity recuperation. The playlist music starts off at 140 beats per minute—more than two beats per second—and over twenty minutes gradually falls to 60 beats per minute (BPM). “It provides a warm mattress of sound that leaves them feeling refreshed and revitalized,” Karageorghis said. Music can be a powerful tool that should be used wisely. Listening with earphones—today’s norm—can cause short-term hearing loss, and long-term hearing damage, like tinnitus. Karageorghis cautions not to use headphones for more than an hour a day, and to keep the volume low enough to easily maintain a conversation with a person close by. Karageorghis has worked with many elite athletes over the years, including world champion Welsh hurdler Dai Greene. For Greene, Karageorghis worked with music producer DJ Redlight in 2012 to make a song specially tailored for Greene’s training called “Talk to the Drum."

Other athletes have discovered music’s potency independently. Nicole Sifuentes, 31, a Canadian middle distance runner and Olympian, said that she inadvertently saw how certain songs could impact her running times during training. “I’m not getting faster,” she said. “But it helps me maintain the pace I want to be at when I’m getting tired.” All this leads me to think that the right music might have improved my strength and endurance levels. But it may not have transformed my sprinting. With or without music, maybe I wasn’t bound for professional sports. For a good workout, check out Costas’ sample workout playlist: Pre-event mental preparation Survivor "Eye Of The Tiger" (109 BPM) Snap! "The Power " (109 BPM) Warm-up Justin Timberlake "Can't Stop The Feeling" (113 BPM) Michael Jackson "The Way You Make Me Feel" (114 BPM) Running John Cafferty "Hearts On Fire" (136 BPM) Bruce Springsteen "Born To Run" (148 BPM) Weight training Clean Bandit "Stronger" (125 BPM) Tiësto "Work Hard Play Hard" (128 BPM) Warm-down Fat Larry's Band "Zoom" (105 BPM) Bill Withers "Lovely Day" (98 BPM) Recuperation/revitalization Stevie Wonder "Ribbon In The Sky" (69 BPM) Joe Cocker "You Are So Beautiful" (62 BPM) [Editor’s Note: A__n__d i__f y__o__u_’r__e i__n t__h__e m__o__o__d f__o__r s__o__m__e__t__h__i__n__g a l__i__t__t__l__e m__o__r__e m__e__d__i__t__a__t__i__v__e,_ c__h__e__c__k o__u__t H__e__a__d__s__p__a__c__e_’_s o__w__n m__e__d__i__t__a__t__i__o__n p__l__a__y__l__i__s__t.]

This piece was produced in partnership with Nike Training Club. To get started on your fitness journey, download the NTC app here.

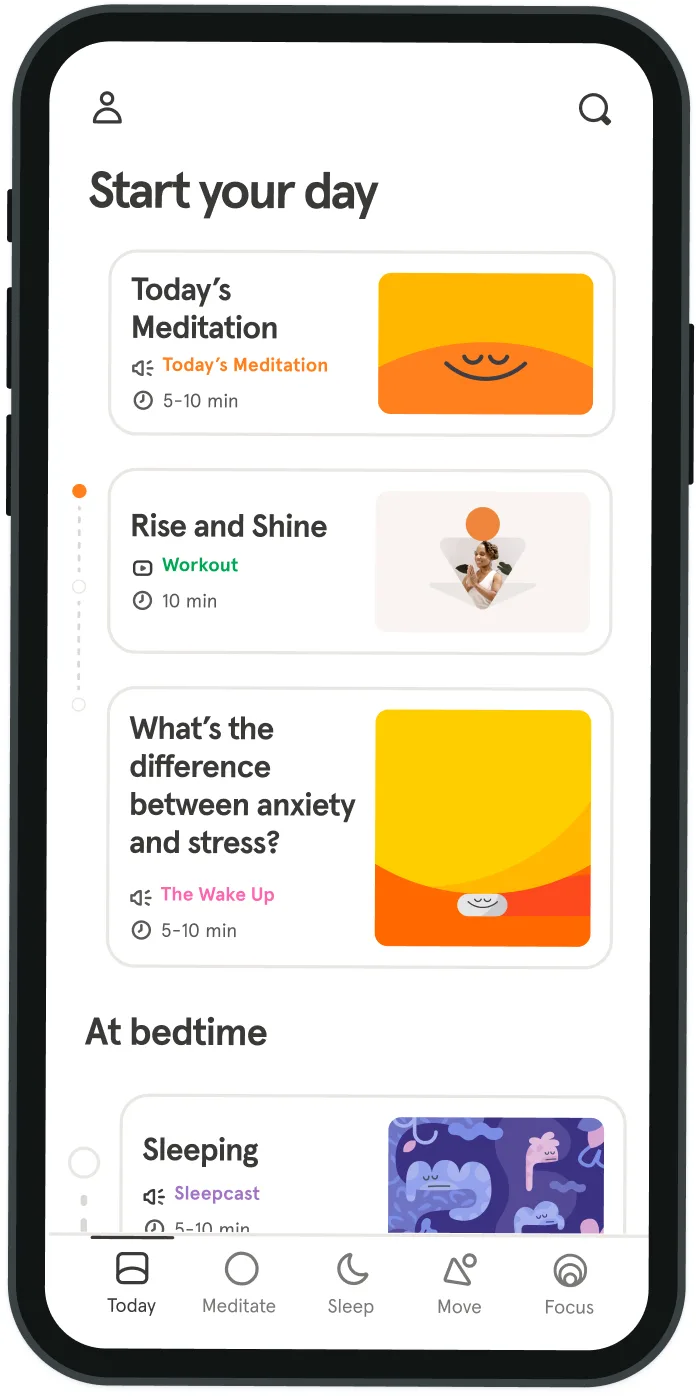

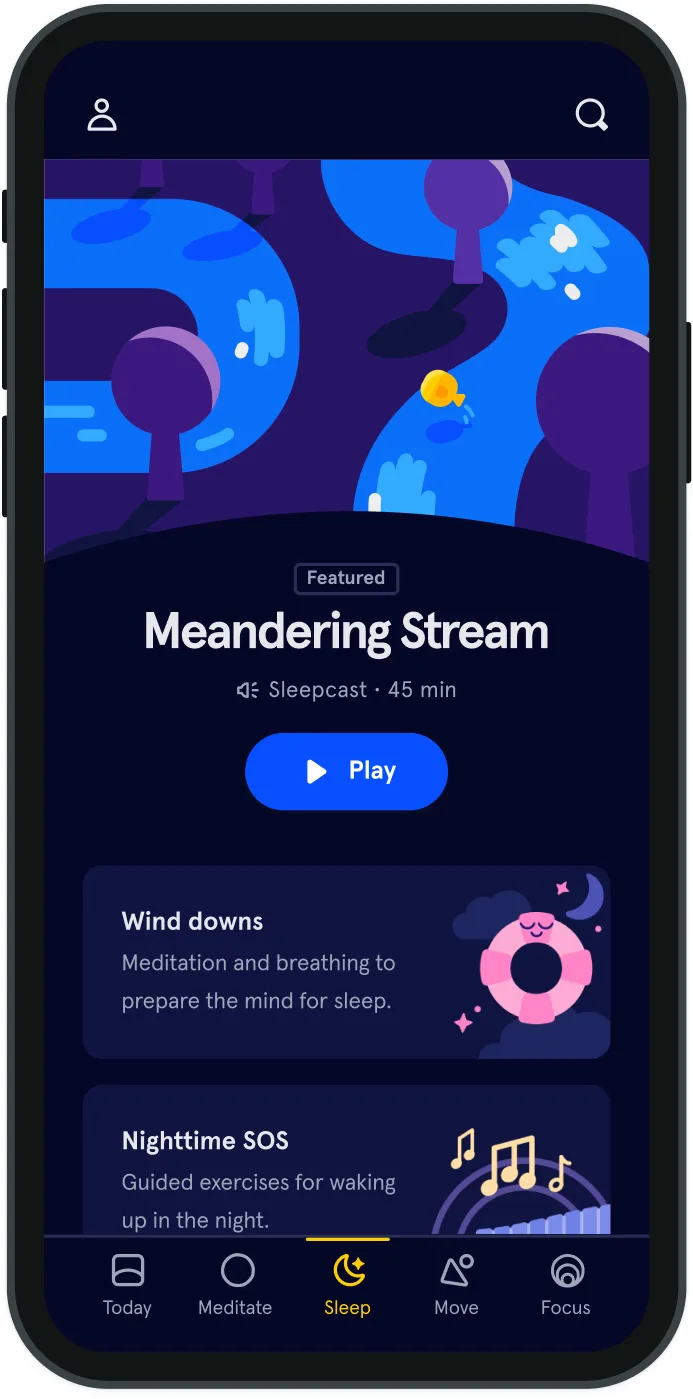

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice