Are you anxious? Or just creative?

As far back as I can remember, I’ve been a writer. And for almost as long, I’ve been a worrier. No surprise there—like any creative profession, writing is a perilous way to make a living. I went into journalism right around the time newspapers and magazines began shedding workers, and for more than ten years, I’ve negotiated the ups and downs of freelancing: hustling for assignments; fretting over late payments; pulling myself back up from many (many!) rejections.

When I began writing a novel—at night, in secret—I indulged in a little positive fantasizing. If I could get an agent, and if the book was published, it might change everything. Maybe at last I’d feel financially secure and creatively fulfilled. Then I’d berate myself for being so unrealistic and go back to worrying. On a minor, suburban scale, I had become the clichéd tortured artist. No, I wasn’t drinking myself unconscious or abandoning my family to live in a hut in the middle of nowhere, but I’d internalized the belief that you couldn’t be creative without suffering. After all, we’re surrounded by images of writers whose work seemed to spring from a well of internal misery, from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s alcoholism to David Foster Wallace’s suicidal depression. One of the most recent, largest-scale studies of the issue, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2011, found that people with bipolar disorder were significantly overrepresented in creative professions (which included university science professors, visual artists, designers and musicians). In an editorial that accompanied the story, Dr. Kay Redfield Jamison, a psychiatry professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, wrote of the “anciently observed thin partition between disease and imagination.”

Dr. Jamison is also the author of an influential book, Touched With Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament, that examines the self-destructive tendencies of writers such as Lord Byron and Sylvia Plath, along with case studies from her own research. But other mental-health professionals have lamented the persistence of such stereotypes, notably psychologist Judith Schlesinger with The Insanity Hoax: Exposing the Myth of the Mad Genius. After all, the vast majority of writers aren’t drugged-out basket cases, but people with families and grounded, normal lives. (You don’t see many dramatic, Byronesque figures swaggering their way through modern-day writers’ conferences—though that might liven things up a bit.) Clearly, I didn’t have the kind of mood disorder that would land me in a mental-health ward. (On the couch in my PJs, eating my way through my kids’ Halloween candy stash? Yes.) Still, I could identify with the emotional arc of bipolar disorder. I knew how it felt to be euphoric one day (“I’m writing something great!”) and hopeless the next (“I’ll never have a good idea ever again”). And always, my worry simmered, a self-doubting whisper I could never quite shut off. But that, I’ve come to learn, isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Worrying isn’t a character flaw or weakness I need to eradicate; it may actually be useful. “Studies have shown that a low level of anxiety is linked to peak cognitive performance,” says Dr. Helen Widlansky, a psychologist in Seattle who works frequently with college students (another anxiety-prone population). “It’s likely that we’re better able to tap into our imagination when we are somewhat anxious or aroused.”

Over time, I’ve come to regard that inner, questioning voice not as the enemy, but as a hardwired feature of creative thinking, something like those built-in apps that come preloaded on your phone, whether you want them or not. If I wasn’t anxious about my future, I wouldn’t be driven to keep working, to try new ideas, to rewrite and refine every sentence until it’s the best I can make it. When I’m fretting about whether and when my next book will be published, I’m using the same mental process I access when I write fiction: imagining different versions of my future, all of which I flesh out until they feel completely real. It will be a huge success, and I can afford a vacation to Europe. It will be a miserable flop, and I’ll become a recluse. I can picture dozens of different outcomes for every action I take, and a dozen ways my life could be better if I’d only done one thing differently in the past. The key is to look at that anxiety as a tool, rather than allowing it to take over. “Anxiety becomes problematic when experienced in extremes,” says Widlansky. “But in the right amount, it’s very helpful.” Rather than worry about my worrying, I’ve learned to view my negative thoughts as the price I pay for a tremendous blessing. Now, whenever I feel uneasy about my career and picture myself applying for a job at the hamburger place in the mall—and being rejected—I recognize that worst-case scenario for what it is: my brain doing its thing. In other words, being creative.

The key is to look at that anxiety as a tool, rather than allowing it to take over

Elizabeth Blackwell

Be kind to your mind

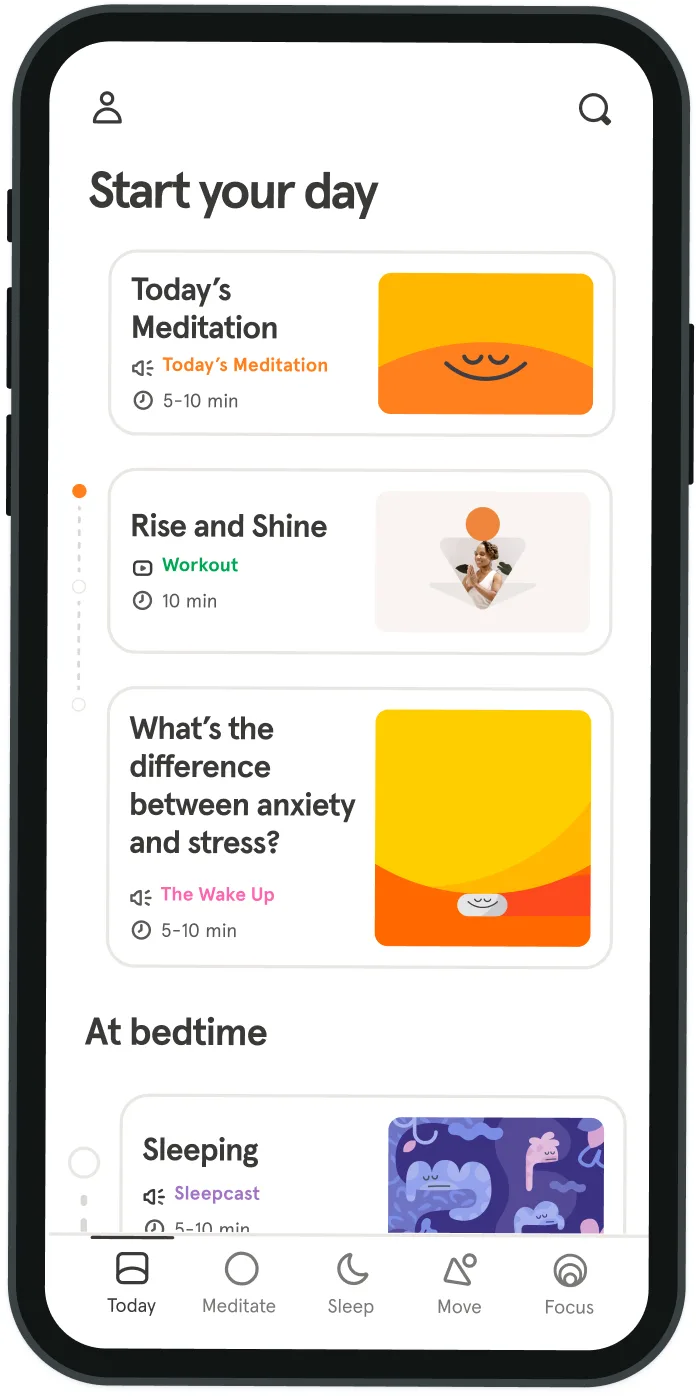

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

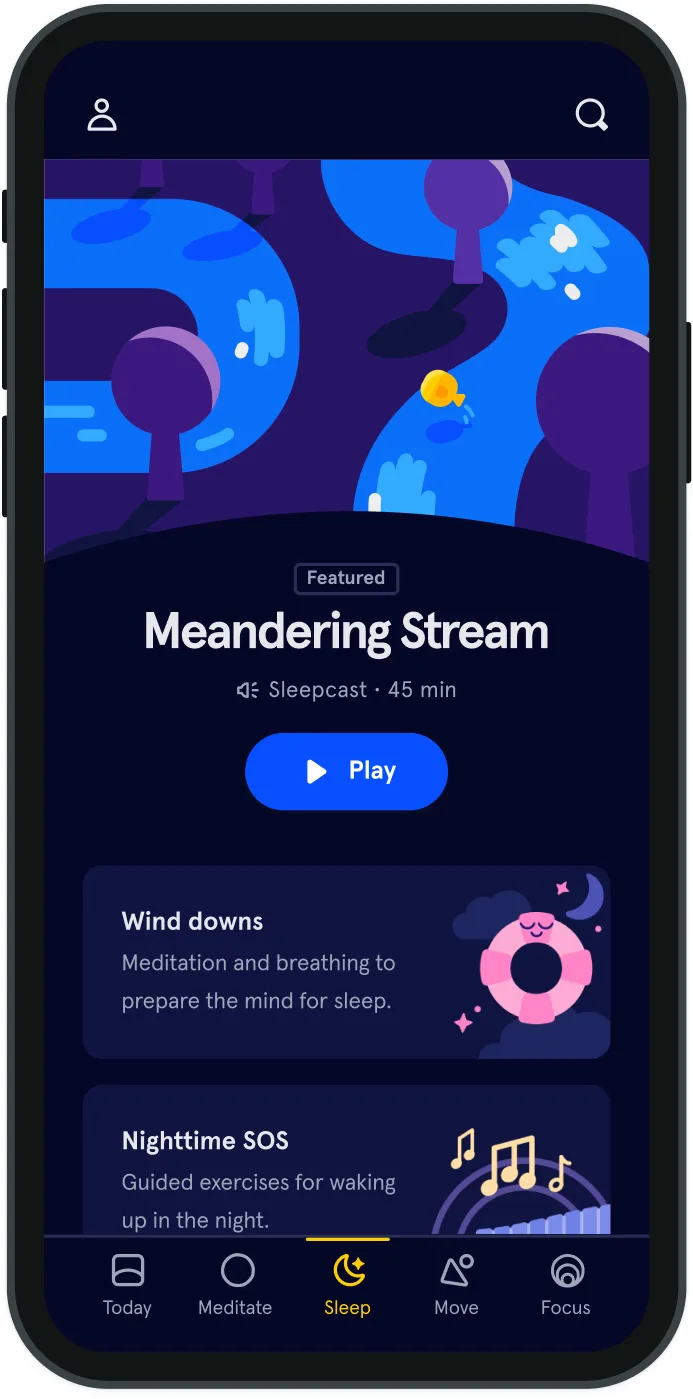

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice