The unexpected benefits of going for a walk

To most people, walking seems—well, pedestrian. Sure, it was the first form of human locomotion, and it set us apart from our primate ancestors, but there’s nothing very spectacular about the act.

It is one of our most perfunctory activities, like breathing or sleeping, carrying us around the house, to the grocery store, through our lives. Even those who monitor their daily step totals with a FitBit are more invested in meeting a health goal than the experience itself. But walking can be much more than simply putting one foot in front of the other. It’s all a matter of how you frame it. The act of walking with purpose has a meditative sense to it, one that’s been recorded by writers and philosophers throughout history. Geoffrey Chaucer described Medieval pilgrims traveling by foot to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral in "The Canterbury Tales"; Cheryl Strayed wrote of a very different personal journey across the Pacific Crest Trail in "Wild". Linking these narratives that have hundreds of years worth of cultural (and linguistic) differences are the same questions of redemption and discovery. What will happen to me if I travel for miles and miles on foot? Will I be the same person at the end? Given how valuable traveling long distance by foot seems to have been for writers and philosophers, it will perhaps come as no surprise that the subject is now being examined by scientists.

Researchers have found that walking recharges our creativity, increases the volume of the hippocampus (the part of the brain responsible for short-term memory), and improves spatial performance. Walking in nature increases the benefits, especially for the urbanites who have a higher risk for depression, anxiety, and mental illnesses: a stroll through the greenery can offer immediate mood improvement. This idea is central to the Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, a term coined by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries in 1982. Today, shinrin-yoku has also come to be known as “forest bathing”—though water has little to do with it. Instead, practitioners are advised to stroll through the forest with one’s senses attuned to the atmosphere. A literature review of studies on shinrin-yoku found that blood glucose levels in diabetic patients decreased during their forest walks, that salivary cortisol levels (a hormone tied to stress) were lower when participants were walking through the forest, and that blood pressure and pulse rate were also lower. “From the perspective of physiological anthropology, human beings have lived in the natural environment for most of the 5 million years of their existence,” wrote the authors. “This is the reason why the natural environment can enhance relaxation.” And of course, there are all the other health benefits related to exercise: lowered risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s, and increased cardiovascular fitness. Even something as simple as walking a different route to work can offer a cognitive boost.

Then there are more intangible benefits of traveling on foot: the ability to observe the world as it is, instead of with the speed of a car, plane, or even bike. As writer Rebecca Solnit observes, “Walking, ideally, is a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord.” Walking allows contemplation, but also freedom. You pick the route and are impeded only when you deem the landscape too treacherous to cross. Like Elizabeth Bennett from "Pride and Prejudice", walking is as much a method of mental escape as it is physical transportation. What problem could she not solve with a long walk through English woods? Of course, in the case of a more traditional journey, the walk is much farther than a stroll to the park or around the block. The distance and time spent on one’s own feet are part of what offers such revelatory experiences. “You’re doing nothing when you walk, nothing but walking. But having nothing to do but walk makes it possible to recover the pure sensation of being, to rediscover the simple joy of existing, the joy that permeates the whole of childhood,” writes French philosophy professor Frederic Gros. That period of pilgrimage, of traveling with purpose but also forcing oneself to live with each step, is like capturing a bit of timelessness. And as Robyn Davidson would argue, it’s what modern Westerners are missing from their lives.

Try it for yourself: Give our guided walking exercises a shot.

Walking allows contemplation, but also freedom.

Lorraine Boissoneault

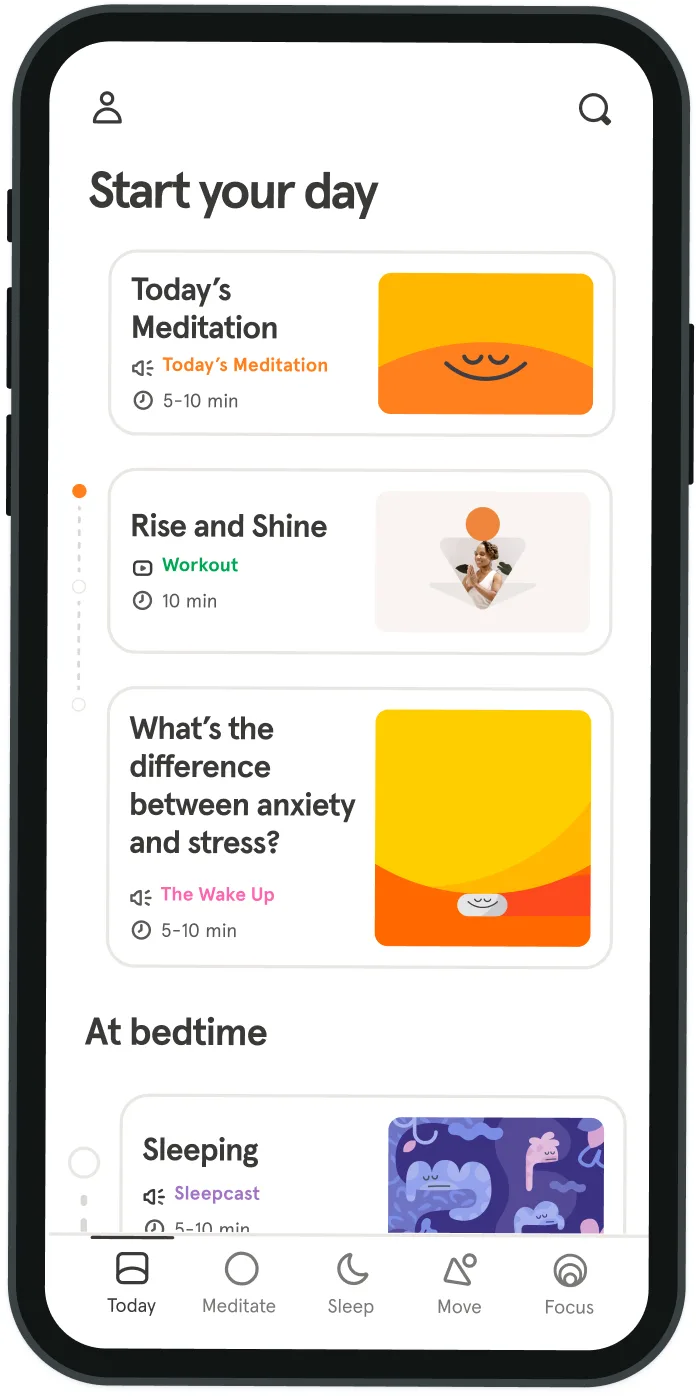

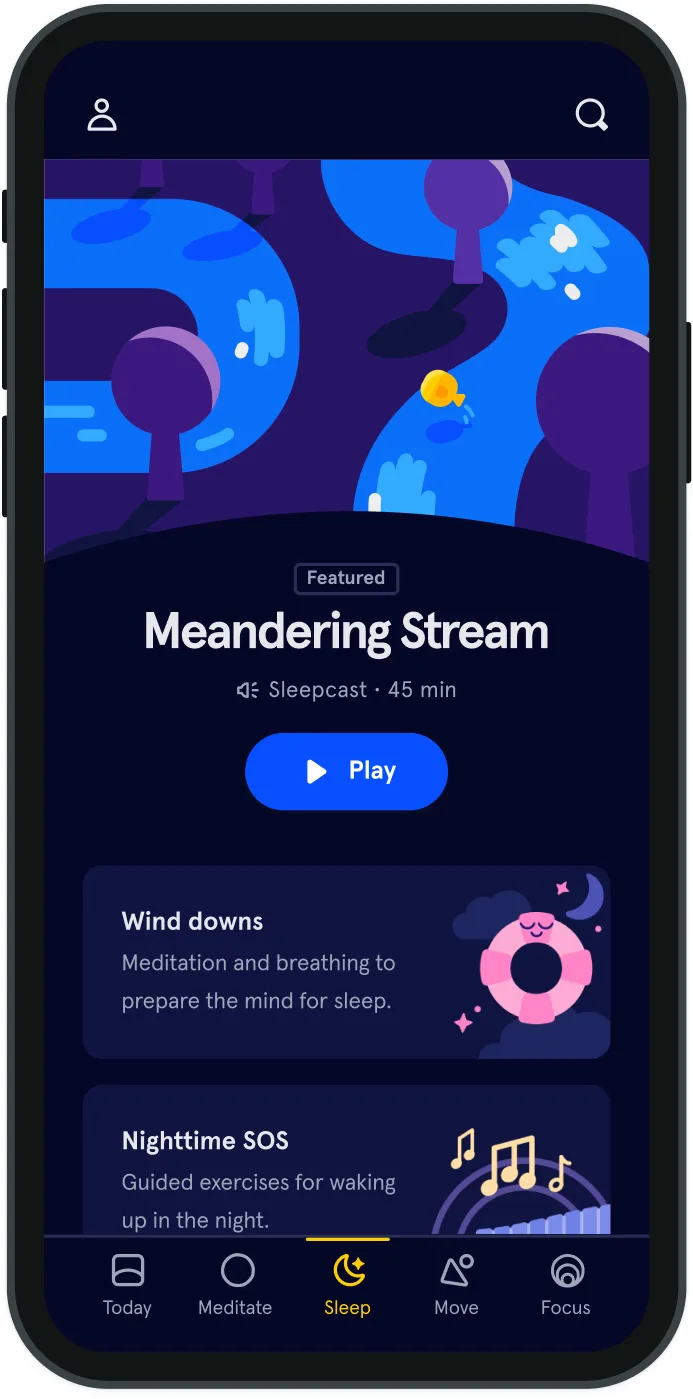

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice