The After Series: Beer Cans in the China Cabinet

We spend so much of our waking lives avoiding death—in more ways than one. When it comes to talking about the inevitable, it isn’t always easy. So the Orange Dot is aiming to shine a light on these stories, in hopes that it may help others. The After Series features essays from people around the world who’ve experienced loss and want to share what comes after.

I never referred to them as Grandma and Grandpa. I didn’t even remember them. Using those words would have made me feel like I was faking affection for my mother’s parents when all I had was a few grainy photos and a gravesite for reference.

I might have wished I was somewhere else. I may have sighed—a lot. But I never rushed her. I’d talk myself out of feeling guilty for not giving a damn by reminding myself that I couldn’t really be upset about strangers being dead. Because really, that’s what they were—right? Right. End of discussion. But now, almost a decade after the untimely death of my own father, I wonder if my own daughter will be rolling her eyes at me every time I want to make a special trip to the cemetery to pay my respects. We won’t be able to go very often, mind you. He’s buried in Detroit, in the plot right next to my mother’s parents, and a far cry from our home in Minnesota. There’s a moment, each year on his birthday and on the day he passed, that we all get melancholy because he’s not here to make us laugh. Or piss us off just so he can make us laugh again. I can’t say “Who died and made you boss”—no matter how appropriate—because my dad did die and he was supposed to always be the boss. I wonder if my daughter will think I’m crazy for not being able to throw away the last can of Miller Lite I found in our recycling bin in our first home, just a few miles from the house he shared with my mother, just because I knew it was his. I used to have two cans, but one didn't survive the move from Tucson to Maine a few years back. I wonder if she’ll ever ask me about him and what he was like. I wonder if she’ll even care. My daughter won’t remember him. She won’t know his face or his voice. She won’t know the devilish twinkle in his eye or how his ears would turn red when he was trying to pull one over on someone. She won’t know that he didn’t tell you he loved you. Or that you knew he did, anyway. I can tell her all of these stories, of course. And she’ll be a good daughter and try to understand. Maybe even empathize. But she won’t really know. I know this because it wasn’t until the moment my father was pronounced dead, just six months into his 50th year and on my mother’s 49th birthday, that I finally understood what my mother had been dealing with all those years when I pretended to care.

So we’d get in the car, drive 30 minutes to Detroit from the suburb where I grew up, and I’d spend just the right amount of time standing beside my mother as she paid her respects before shuffling off to listen to the car radio or paint my nails and wait for them to dry while Mom lingered. She knew I wasn’t going to rush her. I may not have understood, but I wasn’t heartless, either. So I’d add a second coat of polish if she was taking longer than usual. I might have wished I was somewhere else. I may have sighed—a lot. But I never rushed her. I’d talk myself out of feeling guilty for not giving a damn by reminding myself that I couldn’t really be upset about strangers being dead. Because really, that’s what they were—right? Right. End of discussion. But now, almost a decade after the untimely death of my own father, I wonder if my own daughter will be rolling her eyes at me every time I want to make a special trip to the cemetery to pay my respects. We won’t be able to go very often, mind you. He’s buried in Detroit, in the plot right next to my mother’s parents, and a far cry from our home in Minnesota. There’s a moment, each year on his birthday and on the day he passed, that we all get melancholy because he’s not here to make us laugh. Or piss us off just so he can make us laugh again. I can’t say “Who died and made you boss”—no matter how appropriate—because my dad did die and he was supposed to always be the boss. I wonder if my daughter will think I’m crazy for not being able to throw away the last can of Miller Lite I found in our recycling bin in our first home, just a few miles from the house he shared with my mother, just because I knew it was his. I used to have two cans, but one didn't survive the move from Tucson to Maine a few years back. I wonder if she’ll ever ask me about him and what he was like. I wonder if she’ll even care.

I knew the story. They had been driving home from a trip to Mexico when a trucker fell asleep at the wheel and ran into their vehicle, head on. My mother, who had just turned 20, lost her parents that day. She was supposed to have been on that trip, she tells me, but she couldn’t bear to leave her 10-month-old daughter for that amount of time. I know it’s a sad story. But because I have no memory of them, I also never allowed myself to feel anything during our yearly treks to the cemetery for birthdays and holidays so my mother could pay her respects. “Time to go to the cemetery for your parents again?” I’d ask when I’d hear my mom on the phone making arrangements for floral blankets and gravesite tags and all that other business that fell into the category of “Stuff I Couldn’t Relate To”. “Yep,” she’d reply. “Can you take me this weekend?”

My daughter won’t remember him. She won’t know his face or his voice. She won’t know the devilish twinkle in his eye or how his ears would turn red when he was trying to pull one over on someone. She won’t know that he didn’t tell you he loved you. Or that you knew he did, anyway. I can tell her all of these stories, of course. And she’ll be a good daughter and try to understand. Maybe even empathize. But she won’t really know. I know this because it wasn’t until the moment my father was pronounced dead, just six months into his 50th year and on my mother’s 49th birthday, that I finally understood what my mother had been dealing with all those years when I pretended to care. It wasn’t until that first trip to the cemetery to visit my father’s grave, right next to that of my grandparents, that I understood what it meant to stand on the very earth that had swallowed my heart. But then I have moments when I think maybe Mom was onto something. Maybe I’ll follow her lead and just let my daughter be. I can’t expect her to feel something for someone she never knew. Or understand the constant ache that’s always there, just under the surface. Or the guilt that comes with living when you know that you just left flowers for someone who’s supposed to still be alive, too.

And because I have my own driver’s license, there’s really no need to force her to tag along when I’m in town and can make a stop at the cemetery with my mother, who’s smarter and stronger than I ever gave her credit for. Because she knew that I didn’t understand and was glad for it. And she was so very devastated when I finally did. I don’t want my daughter to know what that feels like. So I won’t say anything when she refers to her grandfather as “your dad.” I try not to cry when she doesn’t. Right now, she is laughing at the rolls of thunder during a rainstorm. My daughter’s laughter is an echo of his own. When she asks me if that means if Guelo just bowled another strike, I nod, not trusting myself to speak. He was mine. And now he also belongs to her.

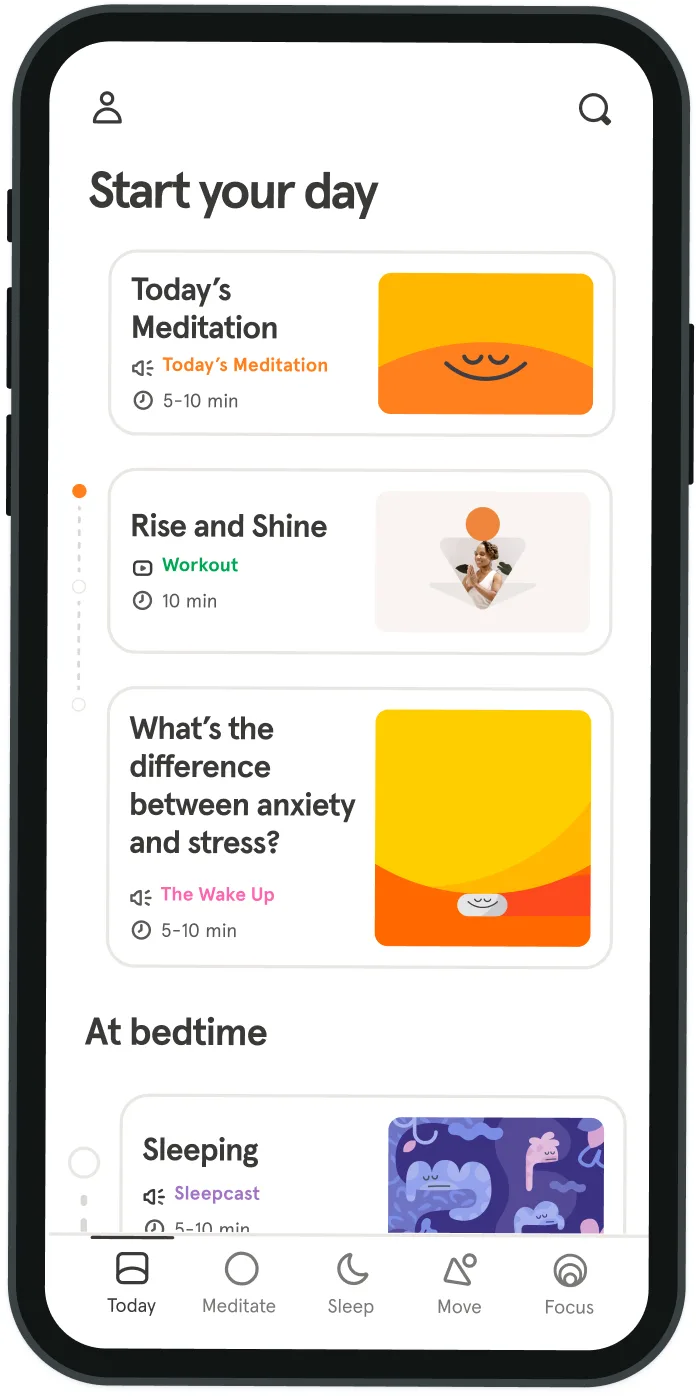

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

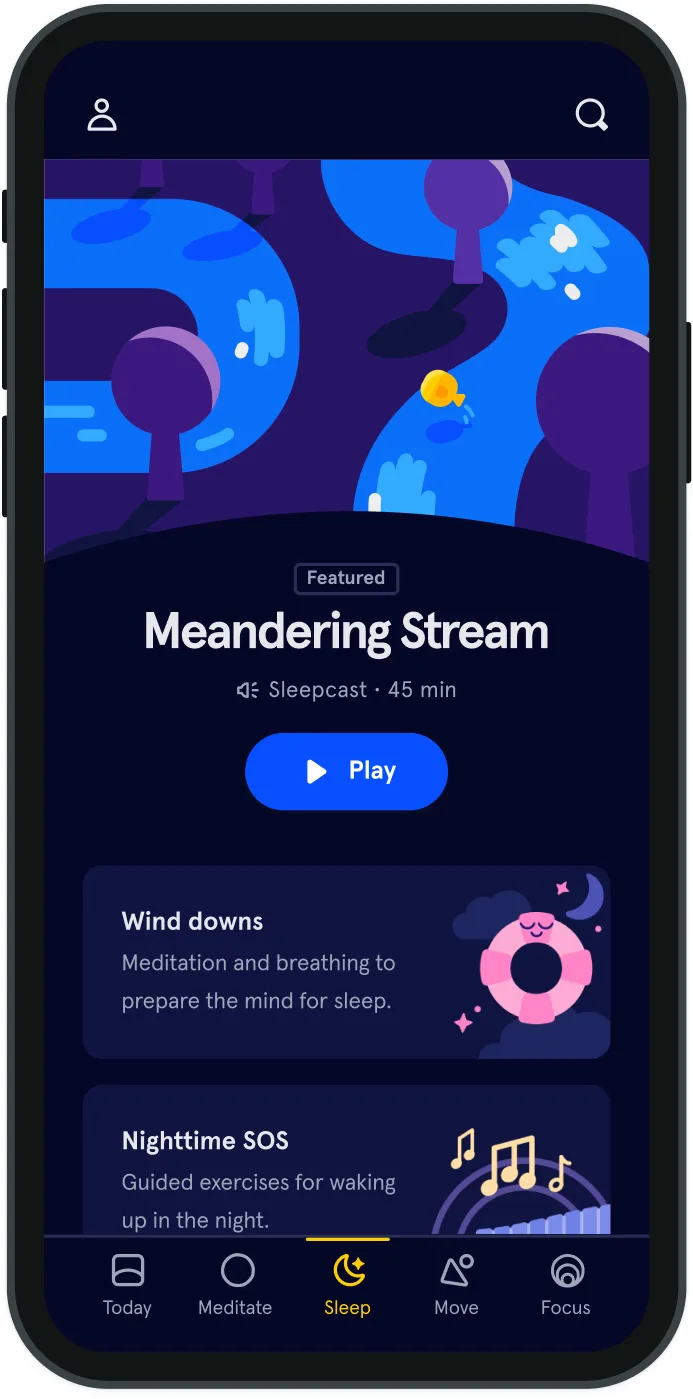

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice