How I learned to stop panicking and love air travel

It was more than a fear. It was an outright, crippling, life-obstructing phobia. And it all began when I was 20 years old.

I was away at college, and my mother called to suggest I come home for the weekend. I contacted friends, made plans, flew home to New York City, and was met at the airport by my then-boyfriend and my sister’s then-boyfriend. They were as dour as pickles. They told me my father was in the hospital and would have brain surgery the following day. They suspected he had brain cancer. The shock to my nervous system when I stepped off the plane was enormous. I was prepared for one thing and hammered with another. The following months launched me into what I later learned was PTSD. The surgeon was all steel and ice, and spoke to my family as though we were flies on the tip of his nose. He let us know that he couldn’t remove the entirety of my father’s fast-growing tumor, and no one survived the type of cancer he had. When I asked if my father would be a vegetable, he shrugged and walked out the door. After the surgery, my vigorous, healthy, athletic, highly intelligent father lay in a hospital bed with a huge lump on his head, his complexion ashen, unable to find the right words. He would say things like: “the important papers are in the hrupgy.” He watched cartoons, slipped in and out of a coma, was catheterized, and didn’t censor what he said. My role was to be the clown. I hitched rides from college to the hospital every week, and as I walked down the long corridor to my father’s room, I tried not to look at the other patients, hooked up to tubes, leaning back in propped-up beds, eating from plastic plates on plastic trays. And when I entered my father’s room, I would brace myself for what horrors I might find. To cheer up my family and my father’s crusty roommate, I acted upbeat, told jokes, and called my father by silly nicknames, while burying my panic and anxiety deeper and deeper.

When my father died, I got a call from my mother, who told me to fly home for the funeral. I was shaking when I got on the plane and quaking uncontrollably when I got off. Another plane flight to the land of misery. It was the last time I flew. For 26 years I was unable to get on a plane, go to an airport, or even look at a photo of a plane without panicking. When I read an article about a plane crash, it stirred me up terribly. [Editor’s Note: if flying is tricky for you, try the Fear of Flying single. I swear by it.] I went (by ship) to live in Europe and stayed for nine years. First I was married to an abusive, lying, cheating man. I guess it was a logical extension of my life since my mother had been an abusive, lying woman. So when my father died, there was nothing between me and my mother’s rage and violence. It all set the stage for severe anxiety and my loss, grief, panic, and helplessness were expressed in my total inability to fly. Every four years, I saved enough money to sail from Europe to the states to visit friends and family. It took 12 days of ocean travel and cut out most of my vacation. Eventually, I decided to deal with it head on: first with a Freudian therapist. Next, I tried hypnosis, and eventually, I tried face-to-face psychotherapy. Result: I spent a quarter of my salary but the flying phobia was as intractable as ever. One summer I sailed home and attended a fear of flying support group at the airport. Some participants had suffered a trauma that related to flying, while others couldn’t point to an experience that triggered their fears. We were taken on a grounded plane, and I broke into a sweat. My pulse shot up and my heart raced. I finally moved back to the U.S., became a screenwriter, and when I traveled for work, it was an Amtrak no-brainer. I still couldn’t beat the flying phobia. I felt I had tried everything. One day, my husband saw a TV segment about Recovery International, a group for recovery from mental health issues, using cognitive behavioral therapy techniques developed by Dr. Abraham Low. The group was open to everyone, free, and held meetings in cities around the U.S.

My husband attended the first meeting with me, and within half an hour I was intrigued and, even more important, hopeful. They shared hundreds of phrases that brilliantly communicated how the nervous system acts when it is in an aroused state. My favorites were, “This is distressing but not dangerous,” “feelings rise and fall and run their course, as long as you attach no danger to them” and “fear is a belief. A belief is a thought. A thought can be changed.” I repeated them over and over, attended meetings weekly, and practiced. And practiced. And when I felt overwhelmed by emotions, in spite of practicing, I repeated the phrase: “Try, fail, try, fail, try, succeed.” And then it happened. I earned a plum writing assignment with one caveat: I had to fly. It was a two-hour flight. I decided to try it, and thought of the phrase: “bear the discomfort in order to gain comfort.” I didn’t sleep for a week, felt shaky when I got on the plane, and when the door closed and the engines started up, I didn’t think I could do it. The plane took off. I didn’t dare look out the window. I stared straight ahead, holding my breath, and then I called up one of the phrases I had been practicing for months. Fear is a belief. A belief is a thought. A thought can be changed. I repeated it over and over, and put my fear of flying in the context of other absurd thoughts. For two hours, I considered absurd things that could happen. The seats would turn into beach chairs. The flight crew was going to fly around like bats. The plane was going to crash. At the end of the flight, my flying phobia was gone. After 26 years, it flew away. And in its place was a living dream. I became an international travel journalist, and, with my photojournalist husband, I now fly all over the world to write and speak about transformative, culturally-rich travel. I have flown in hot air balloons, helicopters, and seaplanes. I have landed on remote airstrips in Micronesia and Polynesia, the Arctic, South America, and everywhere in between. Do I feel calm in a plane? Generally, except when there is turbulence. Then I turn to my husband and ask, “What’s happening?” He reminds me it’s like being on the ocean. The turbulence passes. I go on with life.

Be kind to your mind

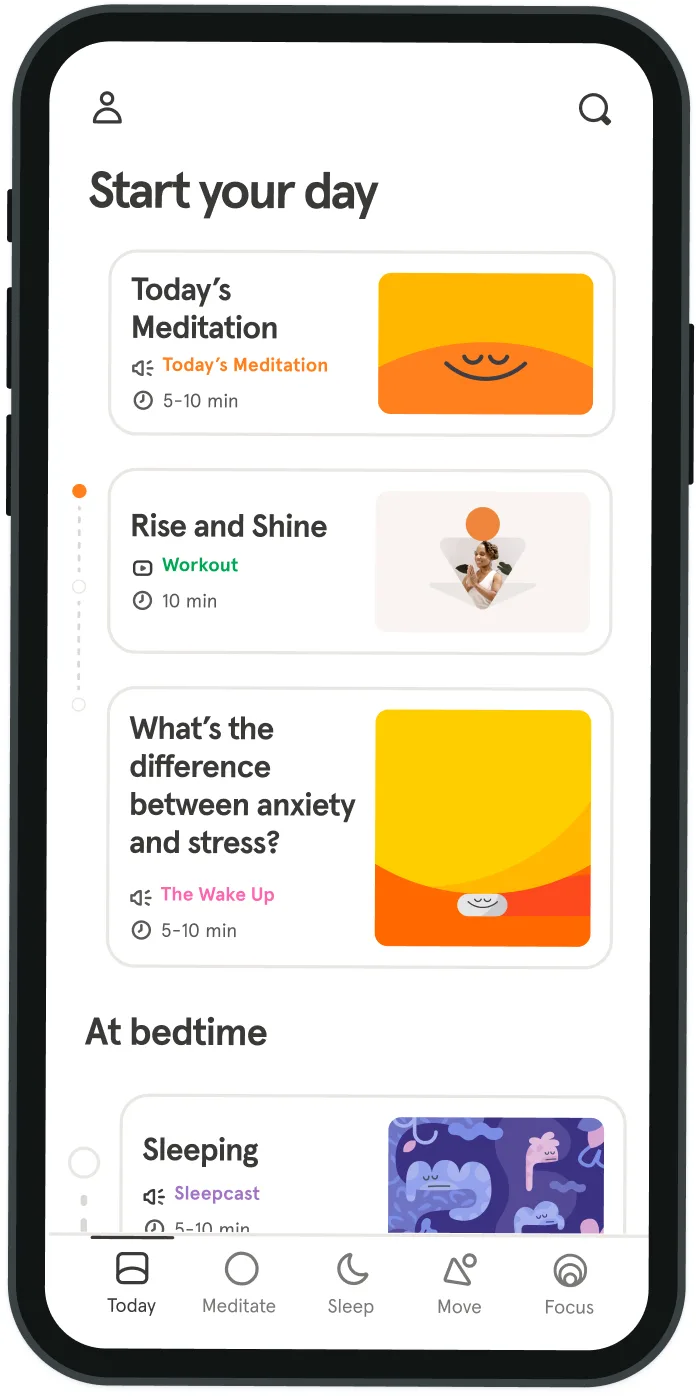

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

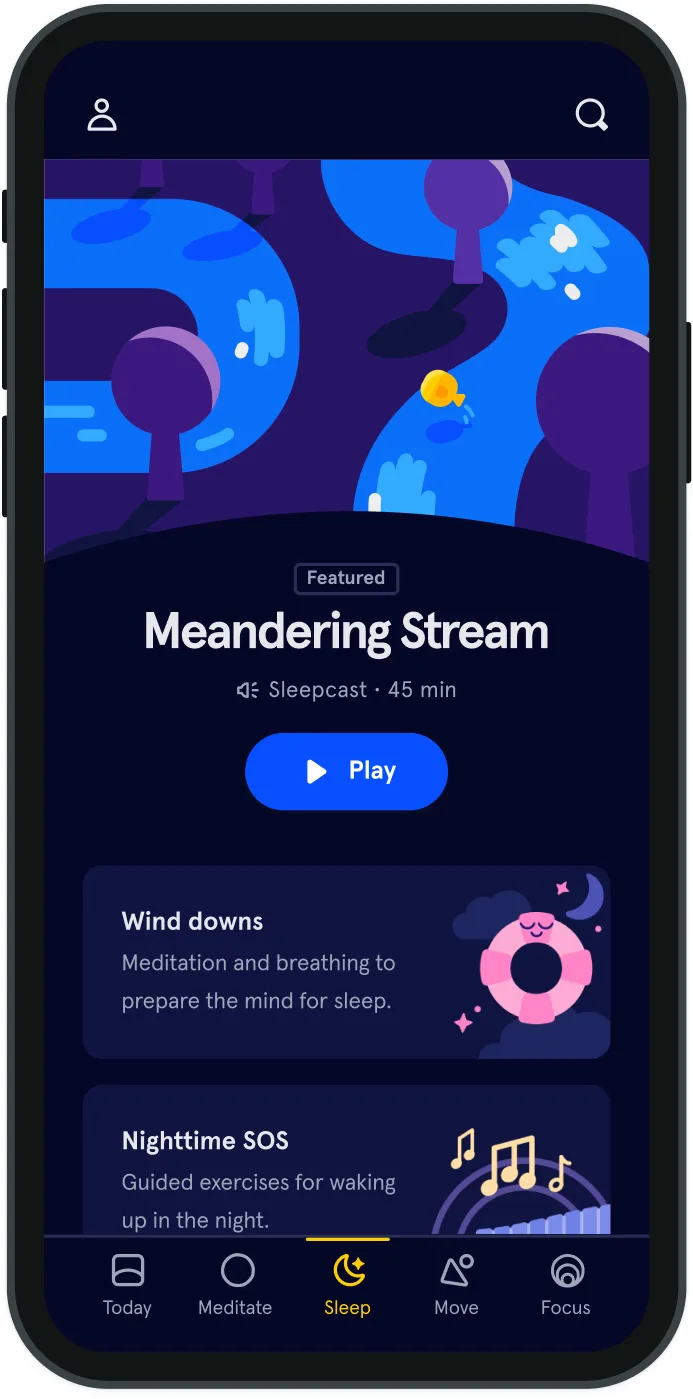

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice