Who gets to be a risk taker?

People often think of risk-takers as daredevils with an inborn desire to put their lives on the line for a thrill. When travel and science writer Kayt Sukel set out to pen her 2016 book, “Art of the Risk,” she anticipated “researching these weird, genetically-different risk-taking superheroes.”

Biology does play a role in our willingness to take risks, but Sukel discovered a variety of other factors—including our familiarity with the risk at hand, age, emotional state, and even whether we make conscious efforts to take more risks. When we take risks, nerves in our brains release dopamine—the same chemical that causes us feel happy when eating, having sex, or taking certain drugs. Researchers have found a correlation between thrill-seeking behavior and a genetic mutation of dopamine receptors. In a 2014 study of around 500 experienced skiers and snowboarders, those who sought greater thrills on the slopes were more likely to a share the mutation, which changes the way the brain processes dopamine and has been called the “adventure gene.” That said, “you don’t need this gene to be a risk-taker,” said Sukel. “It’s just one small piece of the puzzle.”

An over-emphasis on genetics is not the only common misconception about risk-taking. Traditionally, researchers measured risk-taking by setting up gambling scenarios, where participants were asked to choose between a small amount of guaranteed money or a chance at a greater amount. Men tended to go for the larger pot, leading scientists to think of risk-taking as a male trait. But instead of proving that men take more risks, gambling-based studies may just demonstrate that men have more experience making high-risk financial decisions. So if you’ve never gambled, but are asked to do so in a research lab, you may perceive the risk as greater than your fellow participant who makes high-profile financial decisions for a living. In fact, familiarity with any activity makes us perceive it as less risky, the way that someone who has been rock climbing for years might take on a new climbing challenge without fear. Similarly, men who traditionally managed family and workplace finances might feel more comfortable making hypothetical financial bets. According to a 2011 review of risk research, “once the differences in perceptions are taken into account, the trade-off coefficient—that is, the risk attitude—does not differ between genders.” “When women were expected to do limited things, how could they do well on these tasks they have no experience in?” said Sukel. “As opportunities open up for women, they are not shying away from risk.” There’s another reason gambling scenarios don’t give us the full picture. Risk-taking is domain-specific, meaning that one person may love skydiving, while another jumps at the chance to move to a new country, and another stands up to injustice. “If you put people in different situations, even your most quiet, demure wallflower can become quite a risk-taker,” said Sukel.

In 2002, psychologists developed the Domain-Specific Risk-Taking (DOSPERT) scale, which measures people’s willingness to take risks in six “domains”: gambling, investing, ethical choices, health and safety, social interaction, and recreation. This scale allows for a much more nuanced picture of who takes risks and why. And while women generally perceive financial risks as higher stakes than their male counterparts, they often perceive social risks, such as moving or expressing unpopular opinions, as less risky than men do. Unsurprisingly, another risk-taking factor is age. Rates of criminal activity (inherently risky behavior) increase during late childhood, peak in the teenage years, decrease in the early 20s and continue to decline throughout adulthood. According to a recent report by the Urban Institute, “often, people who engage in risky behavior or in crime as adolescents or young adults ... naturally age out of that.” But even the well-known fact that adolescents take risks isn’t as simple as it seems. In a test called the Columbia Card Task, participants are asked to flip over a series of cards, each of which will either add to their running point total or subtract a large number of points and end the game. When adolescents are asked to choose the number of cards they want to flip over in advance (the “cold” version of the test), they perform as well as adults. But when they have to choose whether to flip over each card as they go (“hot” version), adolescents take more risks and end up with fewer points than adults. These results suggest that teens are fully capable of making rational, calm decisions involving risk—but make riskier decisions in the heat of the moment.

Young people aren’t the only ones whose risk-taking varies with their emotional state. Adults also make riskier choices in the “hot” version of the test—although the difference is less pronounced than with adolescents. “Emotion impacts decisions about risk-taking in all age groups, not just adolescents,” lead researcher Bernd Figner said in a press release. “And the emotion doesn’t necessarily have to be triggered from the decision situation itself. For example, if you’re angry about an argument, you might later drive too fast on the highway.” Certain risks—such as driving too fast on the highway—may not be worth taking. But avoiding risks at all costs is also a bad idea: risk is necessary for personal growth and can lead to novel experiences. Trying a new hobby can bring a lifetime of enjoyment, moving to a new city can lead to new friends and experiences, and advocating for yourself at work can result in a promotion. When it comes to weighing risks and making decisions, practice pays off. According to an article in the Harvard Business Review, “business courage is not so much a visionary leader’s inborn characteristic as a skill acquired through decision-making processes that improve with practice.” Successful leaders aren’t just born with an ability to make high-risk decisions—it is a skill they honed over many years of experience. Sukel said that when we talk about risk, “we tend to make it seem like it’s all about extreme sports or billion-dollar business deals, as opposed to something that’s really part and parcel of every single decision we make every single day.” She recommends taking small steps to push yourself out of your comfort zone, like trying a new restaurant, reading a new type of book, or taking on a new challenge at work. “We get into habits, we get into ruts,” she said. Taking risks can help shake us out of our routines. “Risk isn’t inherently bad, risk isn’t inherently good, but risk is necessary,” said Sukel. “It’s such an integral component to learning and growth. It’s really important for people to start integrating more small risks and building up from there in their lives—not just from a learning perspective, but from a joy and enjoyment perspective too.”

Be kind to your mind

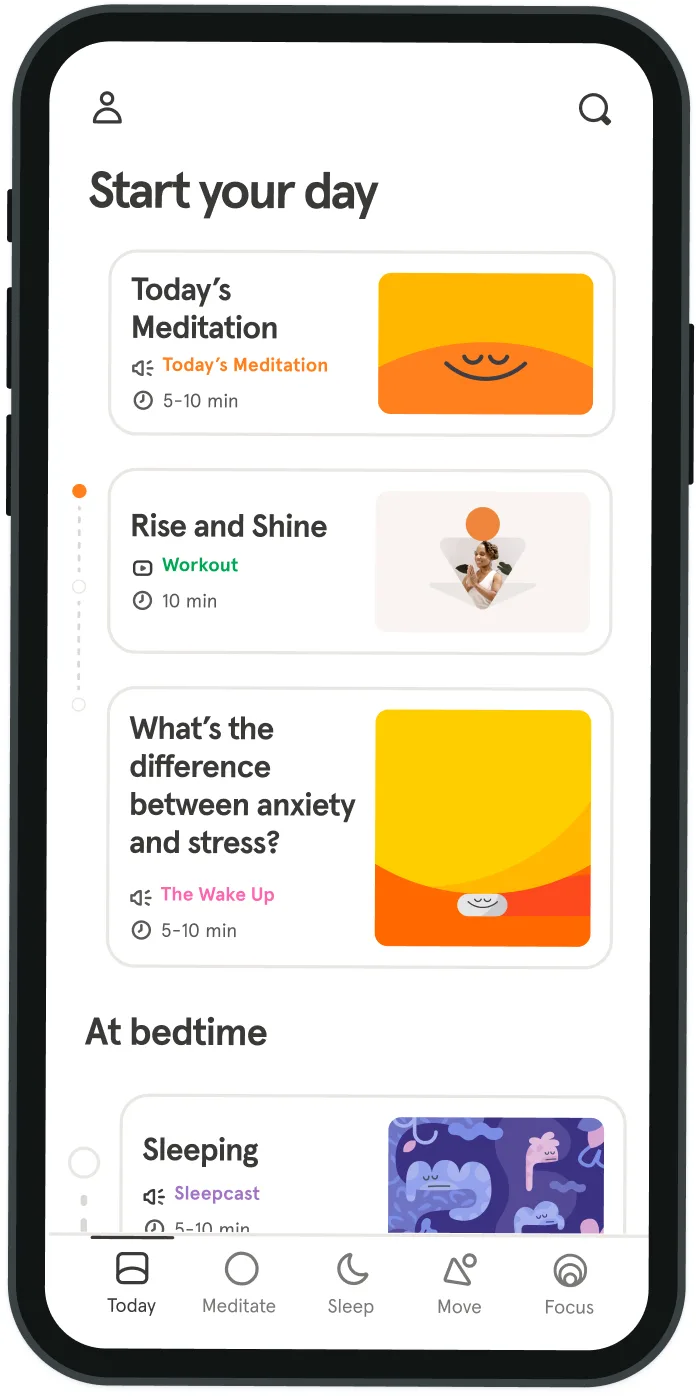

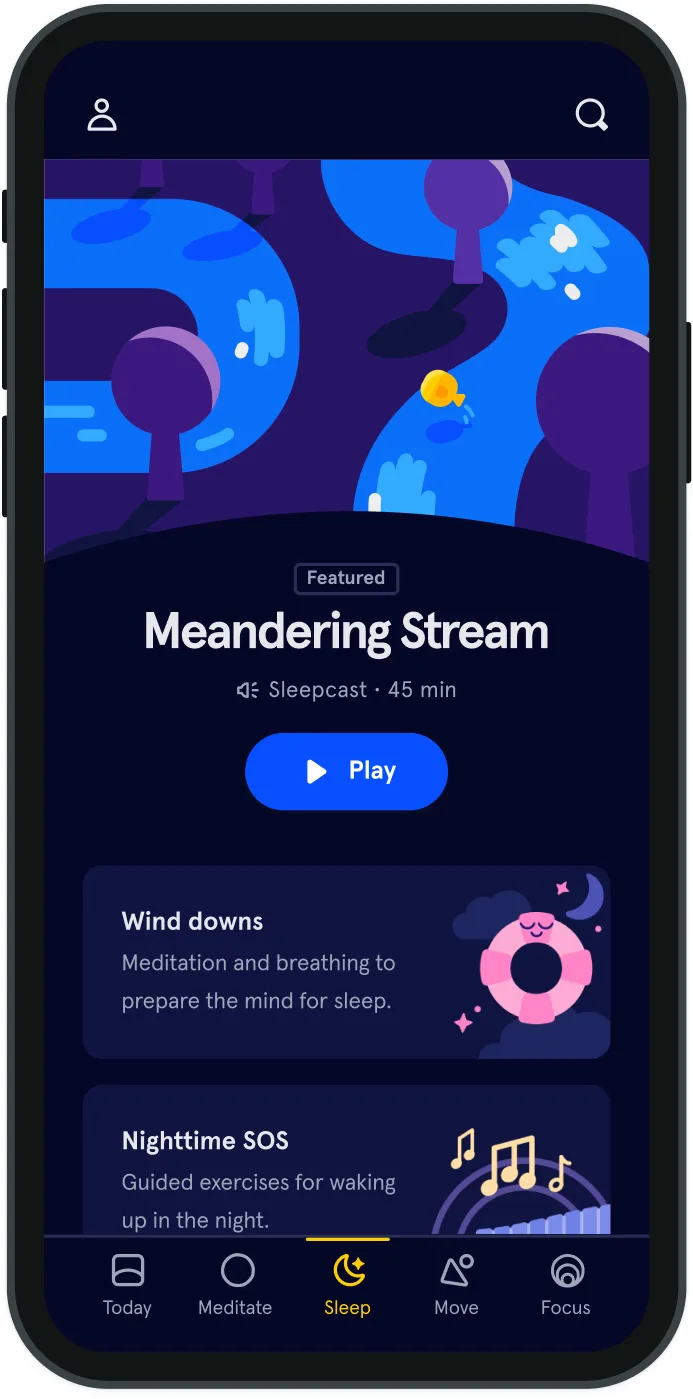

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice