Is it normal to wake up in the middle of the night?

You wake up in the middle of the night and check your bedside clock. Ugh. You’re not supposed to be up for another five hours.

So you struggle to return to slumber—it can last an hour or more, and questions ricochet like rubber pellets around your brain, why is my body doing this to me? Will I be able to function in the morning? Is there some Ancient Greek goddess in charge of this stuff that I could make an offering to? It’s called middle of the night insomnia, and it afflicts as much as 35 percent of the population at least a few times a week. Insomnia is serious business—it can increase the risk of stroke, obesity, depression, and a plethora of other conditions. But sleep researchers have found that middle of the night insomnia might not be a disorder at all.

It might be a vestige of a lost human past intrusively echoing into the modern world. In fact, researchers have discovered that, historically, waking in the middle of the night was the norm in the West, and across most societies spanning every continent (except Antarctica, of course). There are various names for it: bimodal sleep, biphasic sleep, and segmented sleep, to name three. Your grandfather’s grandfather almost certainly slept like this. If he didn’t, he certainly knew someone who did. Until recently, however, this has been largely forgotten knowledge. A. Roger Ekirch, a history professor at Virginia Tech, was deep into researching his 2005 book, “At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past”, a study of nighttime life throughout history, and dreaded having to research a chapter about sleep. He worried about creating a chapter’s worth of new and interesting insight. People hit the sack (or the straw), and then woke in the morning—so what? To his astonishment, there was a wealth of material to mine. He quickly discovered that for much of recorded history, and probably before that, people in the West slept in two cycles. They called it first sleep and second sleep, and they spent an hour or so awake in between. “You can imagine my delight when I started finding dots and connecting dots that led me to the conclusion that people slept very differently,” Ekirch said.

Pouring over centuries-old English court depositions, he found numerous references to a first sleep and second sleep (historians often look at court documents not just to research crimes and disputes, but also to see what the documents reveal about daily life of the period). In the court documents, people also spoke of how, during the wakefulness period, they ruminated over dreams to which they attached great importance. They also did other things like sew, pray, steal a neighbor’s firewood, or make love—the wakefulness time was regarded a particularly auspicious hour to bear fruit and multiply. “I realized it was something I had never heard of,” Ekirch said. First and second sleep were mentioned casually in the documents, which also revealed it to be unremarkable, a daily facet of the human experience. Ekirch then turned to literature. The oldest reference, he found was in Homer’s Odyssey, believed to have been composed in the eighth century BCE. (Poseidon’s servant Proteus takes a “first sleep”). He also found a reference hiding in plain sight in the Roman epic poem, “The Aeneid”, from the first century BCE. Virgil describes women after the “first slumber,” when, “night her middle race had rode.” Ekirch found dozens of mentions of first and second sleep, from Charles Dickens and Washington Irving to Alexander Pushkin and Leo Tolstoy and thousands of references in dozens of languages, from the Middle Ages to The Enlightenment. Anthropologists have also documented segmented sleep among the Tiv people of Nigeria, Woolwa people of Central America, and Maroon communities in Suriname. While Ekirch unearthed bimodal sleep references from history, a prominent sleep scientist awakened the sleep science community. In a month-long experiment in 1992, Thomas Wehr of the US National Institute of Mental Health restricted 15 test subjects to 10 hours of daily light. He found that within weeks, most of the subjects drifted into a bimodal sleep pattern, meaning: when not exposed to artificial light, it could be a more natural way of sleeping.

While there is some evidence that it might not be a universal sleep pattern, it’s become accepted by the sleep science community today as the way most people slept for much of human history. It would probably still be the dominant sleep pattern if it weren’t for scientific progress. The Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and 19th centuries walloped people out of two-stage slumber. As science moved toward artificial light, sleep-onset similarly delayed. Gaslight allowed people to stay up into the wee hours. Before this, only the very rich could afford expensive candles and oil and stay up with any consistency. Then Thomas Edison zapped the world with the light bulb, making it even easier, and more widespread, to stay up all hours of the night. Factories also sprang up, and there were enormous movements of people from the countryside to cities, in pursuit of work. Factory workers commonly endured 14- and 16-hour work shifts, which limited the window for sleep for factory workers. Before the Industrial Revolution, middle- and upper-class attitudes toward sleep had begun to morph. In a quest for efficiency and greater productivity, the many people began eliminating second sleep. Instead, they went to bed later and slept until five in the morning or dawn, according to Ekirch. Then they dove right into work. “The workaholic mindset is not new at all,” Ekirch said. By the time the Wright brothers invented the airplane in 1903, the bi-modal sleep pattern in the West only lingered in especially isolated rural areas. It had been eliminated so thoroughly that younger generations forgot it even existed. “By the early 20th century, wakefulness in the middle of the night was no longer recognized as being at all natural,” Ekirch said. But despite the research showing how normal waking in the middle of the night has been over human history, there’s no winding back the clock.“There’s no going back unless you want to live like the Unabomber in a shack in the Yukon without the benefit of electric light,” Ekirch said. And that’s probably OK. “People need to be told that the amount of sleep we need is a 24-hour requirement,” says Adrian Williams, Professor of Sleep Medicine, at King's College, London. “So you can take it however you’d like.”

Williams said that the amount of sleep one needs is genetically determined. The average is eight hours—some people need more, some less. “If you have an interrupted night and you can make up for it in some way (like a nap), that’s probably okay,” Williams says. He emphasized the need for people to get the right amount of sleep, as it broadly impacts health. Lack of sleep has been shown to lead to obesity, diabetes, and all sorts of other ailments. Nevertheless, small subcultures of the population appear to be experimenting with segmented sleep. There’s a Polyphasic Sleep Society online, along with a Reddit forum. Artists and other creative types, as well, have reported turning to segmented sleep because they feel it heightens creativity. In his 2013 book, “Daily Rituals: How Artists Work”, Mason Currey found that many artists had independently arrived at a two-stage sleep schedule because they felt especially creative at night. Lily Hart, 34, a high school foreign language teacher and poetry enthusiast, has experienced this firsthand. She’s dealt with middle of the night insomnia for ten years and recently began writing poetry when waking and unable to drift back to sleep. She found herself approaching language in a different way. “It was 45 percent cool and 55 percent crazy,” she said. “Some of the poems I really liked and some of them were awful.” She first learned of the history of bimodal sleep about five years ago and said she found it comforting. It’s not that bi-modal sleep is better for you, it’s that knowledge of it brings people relief, Erkich has found. He receives emails in which people admit to no longer “feeling like a freak,” after coming across his work; so too, Ekirch’s findings have become widely accepted among sleep researchers. The ancient Greeks, in the end, didn’t have a goddess devoted to waking in the dead of night because they didn’t see it as a problem. That it’s something that plagues us is a symptom of how we haven’t quite adapted to the modern world we’ve created.

Your grandfather’s grandfather almost certainly slept like this.

Benjamin Peim

The workaholic mindset is not new at all.

Benjamin Peim

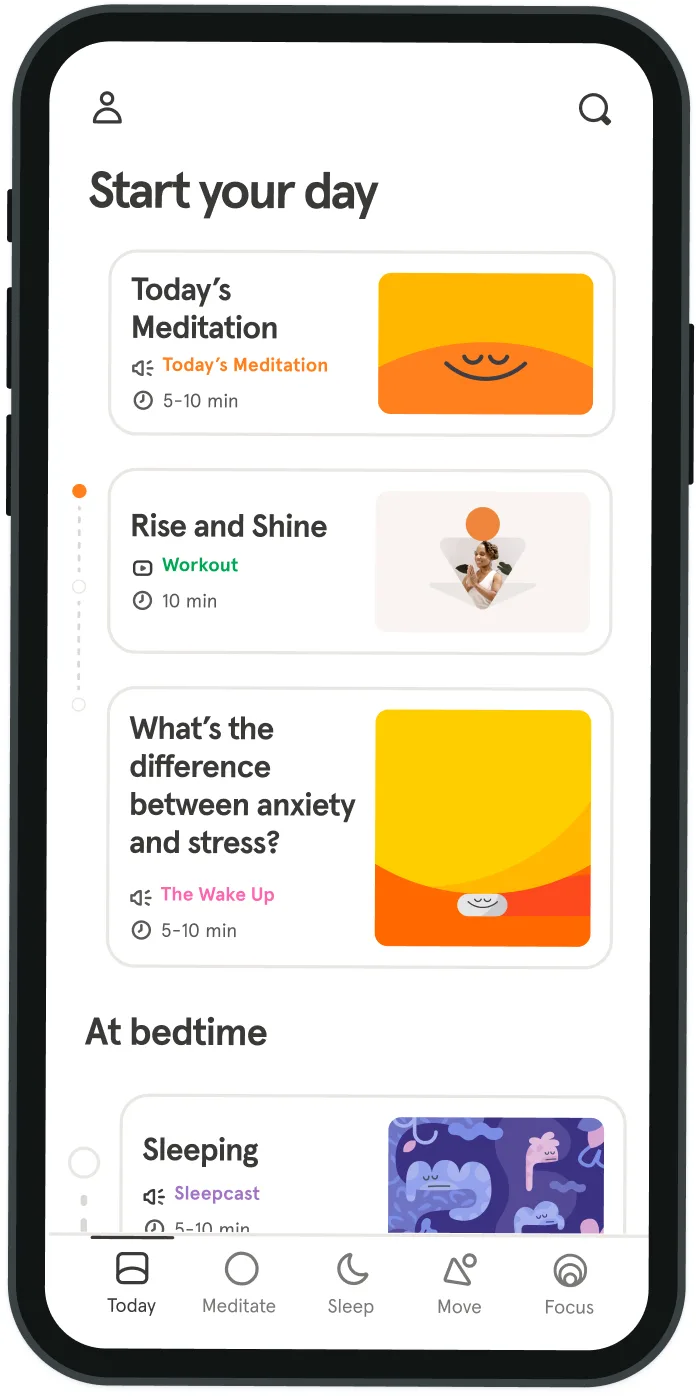

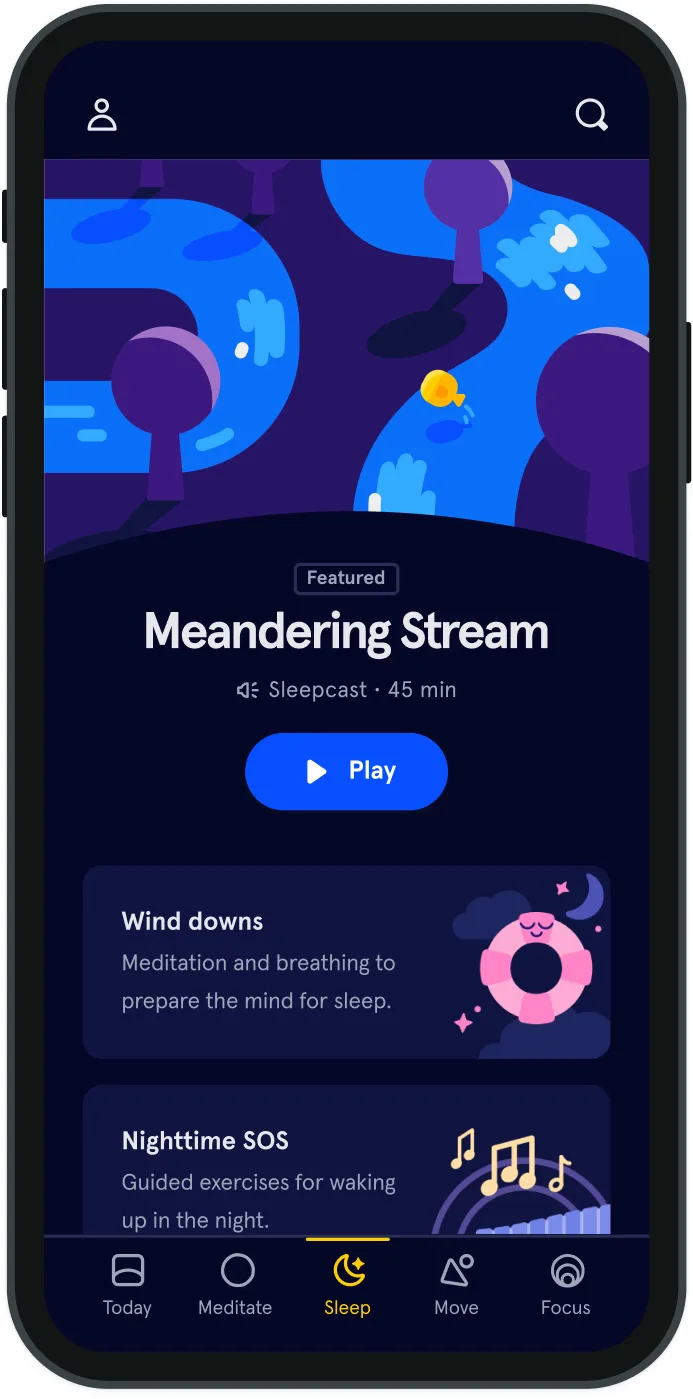

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice